Establishment and validation of a clinical prediction model for infection risk at the placement sites of skin and soft tissue expanders

-

摘要:

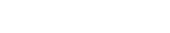

目的 构建皮肤软组织扩张器(以下简称扩张器)置入部位感染风险的临床预测模型并验证其预测价值。 方法 采用回顾性观察性研究方法。纳入符合入选标准的2009年1月—2018年12月于空军军医大学第一附属医院整形外科行皮肤软组织扩张术患者2 934例,其中男1 867例、女1 067例,中位年龄18岁,行皮肤软组织扩张术3 053例次,置入扩张器4 266个。以患者年龄、性别、婚姻状况、民族、入院方式、手术指征、患病时间,有无吸烟史、饮酒史、输血史、基础疾病史、因过敏无法使用头孢菌素类抗生素,单次置入扩张器数量、扩张器额定容积、扩张器首次注水率、扩张器置入部位、麻醉方式、手术时长、有无术后血肿清除为预测变量,以扩张器置入部位感染为结局指标。对数据采用最小绝对值压缩和选择算法(LASSO)回归行单因素分析,筛选影响扩张器置入部位感染的可能危险因素;对单因素分析筛选出的因素行二分类多因素logistic回归分析,筛选影响扩张器置入部位感染的独立危险因素并建立发生扩张器置入部位感染的列线图预测模型。使用C指数和Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验评价模型的区分度和准确度,采用自助重采样法进行内部验证。 结果 LASSO回归分析显示,年龄、性别、入院方式、手术指征、患病时间、饮酒史、心脏病史、病毒性肝炎史、高血压史、因过敏无法使用头孢菌素类抗生素、单次置入扩张器数量、扩张器额定容积、扩张器置入部位、术后血肿清除为影响扩张器置入部位感染的可能危险因素(回归系数= - 0.005、0.170、0.999、0.054、0.510、 - 0.003、0.395、 - 0.218、0.029、0.848、 - 0.116、0.175、0.085、0.202)。二分类多因素logistic回归分析显示,男性、急诊入院、患病时间≤1年、因过敏无法使用头孢菌素类抗生素、扩张器额定容积≥200 ml且<400 mL或≥400 mL、扩张器置入部位为躯干或四肢等是扩张器置入部位感染的独立危险因素(比值比=1.37、3.21、2.00、2.47、1.70、1.73、1.67、2.16,95%置信区间=1.04~1.82、1.09~8.34、1.38~2.86、1.29~4.41、1.07~2.73、1.02~2.94、1.09~2.58、1.07~4.10,P<0.05或P<0.01)。评价模型区分度的C指数=0.63(95%置信区间=0.59~0.66),评价模型准确度的Hosmer-Lemeshow拟合优度检验,P=0.685。自助重采样法内部验证模型的C指数=0.60。 结论 男性、急诊入院、患病时间≤1年、因过敏无法使用头孢菌素类抗生素、扩张器额定容积≥200 mL、扩张器置入部位为躯干或四肢是扩张器置入部位感染的独立危险因素,基于这些因素构建的扩张器置入部位感染风险的临床预测模型构建成功,并具有一定的预测效能。 Abstract:Objective To establish a clinical prediction model for infection risk at the placement sites of skin and soft tissue expanders (hereinafter termed as expanders) and to validate the predictive value of the model. Methods A retrospective observational study was conducted. Totally 2 934 patients who underwent skin and soft tissue dilatation surgery in the Department of Plastic Surgery of the First Affiliated Hospital of Air Force Medical University from January 2009 to December 2018 and met the selection criteria were included. There were 1 867 males and 1 067 females, with a median age of 18 years. Totally 3 053 skin and soft tissue expansion procedures were performed with 4 266 expanders implanted. The following indexes were selected as predictor variables, including patients' age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, hospital admission, surgical indication, disease duration, with/without history of smoking, history of drinking, history of blood transfusion, history of underlying diseases, and inability to use cephalosporin antibiotics due to allergy, number of expander in a single placement, rated volume of expander, water injection rate of expander in the first time, placement site of expander, anesthesia method, duration of operation, and with/without postoperative hematoma evacuation, and infection at the placement site of expander as the outcome variable. Univariate analysis of the data was performed using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression to screen the potential risk factors affecting infection at the placement sites of expanders, the factors selected by the univariate analysis were subjected to binary multivariate logistic regression analysis to screen the independent risk factors affecting infection at the placement sites of expanders, and a nomogram prediction model for the occurrence of infection at the placement sites of expanders was established. The C index and Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test were used to evaluate the discrimination and accuracy of the model, respectively, and the bootstrap resampling was used for internal verification. Results The results of LASSO regression showed that age, gender, hospital admission, surgical indication, disease duration, history of drinking, history of heart disease, history of viral hepatitis, history of hypertension, inability to use cephalosporin antibiotics due to allergy, number of expander in a single placement, rated volume of expander, placement site of expander, postoperative hematoma evacuation were the potential risk factors for infection at the placement sites of expanders (regression coefficient= - 0.005, 0.170, 0.999, 0.054, 0.510, - 0.003, 0.395, - 0.218, 0.029, 0.848, - 0.116, 0.175, 0.085, 0.202). Binary multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that male, emergency admission, disease duration ≤1 year, inability to use cephalosporin antibiotics due to allergy, rated volumes of expanders ≥200 mL and <400 mL or ≥400 mL, and expanders placed in the trunk or the limbs were the independent risks factors for infection at the placement sites of expanders (odds ratio=1.37, 3.21, 2.00, 2.47, 1.70, 1.73, 1.67, 2.16, 95% confidence interval=1.04 - 1.82, 1.09 - 8.34, 1.38 - 2.86, 1.29 - 4.41, 1.07 - 2.73, 1.02 - 2.94, 1.09 - 2.58, 1.07 - 4.10, P<0.05 or P<0.01). The C index for evaluating the discriminative degree of the model was 0.63, the Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness of fit test for evaluating the accuracy of the model showed P=0.685, and the C index for internal validation by the bootstrap resampling was 0.60. Conclusions Male, emergency admission, disease duration ≤1 year, inability to use cephalosporin antibiotics due to allergy, rated volume of expander ≥200 mL, and expanders placed in the trunk or the limbs are the independent risk factors for infection at the placement sites of expanders. The clinical prediction model for infection risk at the placement sites of expanders was successfully established based on these factors and showed a certain predictive effect. -

Key words:

- Dilatation /

- Infection /

- Skin and soft tissue expander /

- Clinical prediction model

-

所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突

-

参考文献

(33) [1] MinP, LiJ, BrunettiB, et al. Pre-expanded bipedicled visor flap: an ideal option for the reconstruction of upper and lower lip defects postburn in Asian males[J/OL]. Burns Trauma, 2020, 8:tkaa005[2021-06-19]. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32341918/. DOI: 10.1093/burnst/tkaa005. [2] KarimiH, LatifiNA, MomeniM, et al. Tissue expanders; review of indications, results and outcome during 15 years' experience[J]. Burns, 2019, 45(4):990-1004. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.11.017. [3] MaX, LiY, LiW, et al. Reconstruction of large postburn facial-scalp scars by expanded pedicled deltopectoral flap and random scalp flap: technique improvements to enlarge the reconstructive territory[J]. J Craniofac Surg, 2017, 28(6):1526-1530. DOI: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003902. [4] HanY, ZhaoJ, TaoR, et al. Repair of craniomaxillofacial traumatic soft tissue defects with tissue expansion in the early stage[J]. J Craniofac Surg, 2017, 28(6):1477-1480. DOI: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000003852. [5] GosainAK, TurinSY, ChimH, et al. Salvaging the unavoidable: a review of complications in pediatric tissue expansion[J]. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2018, 142(3):759-768. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004650. [6] HuangX, QuX, LiQ. Risk factors for complications of tissue expansion: a 20-year systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Plast Reconstr Surg, 2011, 128(3):787-797. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182221372. [7] BjornsonLA, BucevskaM, VerchereC. Tissue expansion in pediatric patients: a 10-year review[J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2019, 54(7):1471-1476. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.09.002. [8] SueGR, SunBJ, LeeGK. Complications after two-stage expander implant breast reconstruction requiring reoperation: a critical analysis of outcomes[J]. Ann Plast Surg, 2018, 80(5S Suppl 5):S292-294. DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000001382. [9] PatelPA, ElhadiHM, KitzmillerWJ, et al. Tissue expander complications in the pediatric burn patient: a 10-year follow-up[J]. Ann Plast Surg, 2014, 72(2):150-154. DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3182a884af. [10] MotamedS, NiaziF, AtarianS, et al. Post-burn head and neck reconstruction using tissue expanders[J]. Burns, 2008, 34(6):878-884. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2007.11.018. [11] As'adiK, EmamiSA, SalehiSH, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing endoscopic-assisted versus open neck tissue expander placement in reconstruction of post-burn facial scar deformities[J]. Aesthetic Plast Surg, 2016, 40(4):526-534. DOI: 10.1007/s00266-016-0644-7. [12] TangS, WuX, SunZ, et al. Staged reconstructive treatment for extensive irregular cicatricial alopecia after burn[J]. Medicine (Baltimore), 2018, 97(52):e13522. DOI: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013522. [13] Abellan LopezM, SerrorK, ChaouatM, et al. Tissue expansion of the lower limb: retrospective study of 141 procedures in burn sequelae[J]. Burns, 2018, 44(7):1851-1857. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2018.03.021. [14] AdlerN, EliaJ, BilligA, et al. Complications of nonbreast tissue expansion: 9 years experience with 44 adult patients and 119 pediatric patients[J]. J Pediatr Surg, 2015, 50(9):1513-1516. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.03.055. [15] TayyabaFU, AminMM, Attaur-RasoolS, et al. Reconstruction of post burn scalp alopecia by using expanded hair-bearing scalp flaps[J]. Pak J Med Sci, 2015, 31(6):1405-1410. DOI: 10.12669/pjms.316.7927. [16] MargulisA, BilligA, EliaJ, et al. Complications of post-burn tissue expansion reconstruction: 9 years experience with 42 pediatric and 26 adult patients[J]. Isr Med Assoc J, 2017, 19(2):100-104. [17] HannaKR, TiltA, HollandM, et al. Reducing infectious complications in implant based breast reconstruction: impact of early expansion and prolonged drain use[J]. Ann Plast Surg, 2016, 76 Suppl 4:S312-315. DOI: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000760. [18] SmolleC, TucaA, WurzerP, et al. Complications in tissue expansion: a logistic regression analysis for risk factors[J]. Burns, 2017, 43(6):1195-1202. DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2016.08.030. [19] HuangYQ, LiangCH, HeL, et al. Development and validation of a radiomics nomogram for preoperative prediction of lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer[J]. J Clin Oncol, 2016, 34(18):2157-2164. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.9128. [20] LaValleyMP. Logistic regression[J]. Circulation, 2008, 117(18):2395-2399. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.682658. [21] AlbaAC, AgoritsasT, WalshM, et al. Discrimination and calibration of clinical prediction models: users' guides to the medical literature[J]. JAMA, 2017, 318(14):1377-1384. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2017.12126. [22] WangH, ZhangL, LiuZ, et al. Predicting medication nonadherence risk in a Chinese inflammatory rheumatic disease population: development and assessment of a new predictive nomogram[J]. Patient Prefer Adherence, 2018, 12:1757-1765. DOI: 10.2147/PPA.S159293. [23] KongL, CaoJ, ZhangY, et al. Risk factors for periprosthetic joint infection following primary total hip or knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis[J]. Int Wound J, 2017, 14(3):529-536. DOI: 10.1111/iwj.12640. [24] ZhangJ, ZhaoT, LongS, et al. Risk factors for postoperative infection in Chinese lung cancer patients: a meta-analysis[J]. J Evid Based Med, 2017, 10(4):255-262. DOI: 10.1111/jebm.12276. [25] AghdassiS, SchröderC, GastmeierP. Gender-related risk factors for surgical site infections. Results from 10 years of surveillance in Germany[J]. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control, 2019, 8:95. DOI: 10.1186/s13756-019-0547-x. [26] GoldMH, McGuireM, MustoeTA, et al. Updated international clinical recommendations on scar management: part 2--algorithms for scar prevention and treatment[J]. Dermatol Surg, 2014, 40(8):825-831. DOI: 10.1111/dsu.0000000000000050. [27] OtaD, FukuuchiA, IwahiraY, et al. Identification of complications in mastectomy with immediate reconstruction using tissue expanders and permanent implants for breast cancer patients[J]. Breast Cancer, 2016, 23(3):400-406. DOI: 10.1007/s12282-014-0577-4. [28] Johnson-JahangirH, AgrawalN. Perioperative antibiotic use in cutaneous surgery[J]. Dermatol Clin, 2019, 37(3):329-340. DOI: 10.1016/j.det.2019.03.003. [29] 常宏, 周毕峰, 崔鑫,等. 整形病区扩张器置入部位感染病原菌分析与感染的临床治疗[J]. 中华整形外科杂志, 2016, 32(3): 191-195. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1009-4598.2016.03.008. [30] RiggioE, ToffoliE, TartaglioneC, et al. Local safety of immediate reconstruction during primary treatment of breast cancer. Direct-to-implant versus expander-based surgery[J]. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg, 2019, 72(2):232-242. DOI: 10.1016/j.bjps.2018.10.016. [31] AzziJL, ThabetC, AzziAJ, et al. Complications of tissue expansion in the head and neck[J]. Head Neck, 2020, 42(4):747-762. DOI: 10.1002/hed.26017. [32] NickelKJ, Van SlykeAC, KnoxAD, et al. Tissue expansion for severe foot and ankle deformities: a 16-year review[J]. Plast Surg (Oakv), 2018, 26(4):244-249. DOI: 10.1177/2292550317749510. [33] DongC, ZhuM, HuangL, et al. Risk factors for tissue expander infection in scar reconstruction: a retrospective cohort study of 2374 consecutive cases[J/OL]. Burns Trauma, 2021, 8:tkaa037[2021-08-01]. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33426134/. DOI: 10.1093/burnst/tkaa037. -

表1 2 934例不同基本资料患者4 266个皮肤软组织扩张器置入部位感染情况(例次)

因素与类别 无感染 感染 LASSO回归系数 年龄(岁) -0.005

<18 1 738 123 ≥18且<40 2 113 132 ≥40 146 14 性别 0.170

女 1 566 90 男 2 431 179 婚姻状况 0

未婚 3 528 233 其他 469 36 民族 0

汉族 3 816 258 其他 181 11 入院方式 0.999

门诊 3 976 263 急诊 21 6 患病时间(年) 0.510

≤1 458 53 >1 3 539 216 吸烟史 0

无 3 928 264 有 69 5 饮酒史 -0.003

无 3 963 267 有 34 2 输血史 0

无 3 863 260 有 134 9 心脏病史 0.395

无 3 974 266 有 23 3 病毒性肝炎史 -0.218

无 3 964 268 有 33 1 高血压史 0.029

无 3 980 267 有 17 2 因过敏无法使用头孢菌素类抗生素 无 3 927 255 0.848 有 70 14 注:置入多个皮肤软组织扩张器患者进行相应例次的指标统计;扩张器置入部位无感染3 997例次,有感染269例次;LASSO为最小绝对值压缩和选择算法;其他婚姻状况指已婚、离异等 表2 2 934例不同手术情况患者4 266个皮肤软组织扩张器置入部位感染情况(例次)

因素与类别 无感染 感染 LASSO回归系数 手术指征 0.054

其他 96 5 瘢痕 2 226 148 体表肿瘤 103 7 黑痣 227 24 外耳畸形 1 345 85 单次置入扩张器数量 -0.116 1个或2个 3 210 226 ≥3个 787 43 扩张器额定容积(mL) 0.175

<200 2 471 141 ≥200且<400 673 53 ≥400 853 75 首次注水率 0

≥10%且<20% 2 326 148 <10% 639 52 ≥20% 1 032 69 扩张器置入部位 0.085

头皮 825 45 面部 593 36 耳后 1 440 88 颈部 194 13 躯干 802 74 四肢 143 13 麻醉方式 0

全身麻醉 1 801 122 局部麻醉 2 196 147 手术时长(min) 0

<60 1 682 111 ≥60 2 315 158 术后血肿清除 0.202

无 3 907 260 有 90 9 注:置入多个皮肤软组织扩张器患者进行相应例次的指标统计;扩张器置入部位无感染3 997例次,有感染269例次;LASSO为最小绝对值压缩和选择算法;其他手术指征主要包括皮肤软组织缺损修复、鼻再造、阴茎再造等;首次注水率=首次注水量÷扩张器额定容积×100% 表3 影响2 934例行4 266个皮肤软组织扩张器置入患者置入部位感染二分类多因素logistic回归分析阳性结果

因素 β值 比值比 95%置信区间 P值 男性 0.32 1.37 1.04~1.82 0.026 急诊入院 1.17 3.21 1.09~8.34 0.023 患病时间≤1年 0.70 2.00 1.38~2.86 <0.001 因过敏无法使用头孢 菌素类抗生素 0.90 2.47 1.29~4.41 0.003 扩张器额定容积(mL) ≥200且<400 0.53 1.70 1.07~2.73 0.026 ≥400 0.55 1.73 1.02~2.94 0.042 扩张器置入部位 躯干 0.51 1.67 1.09~2.58 0.020 四肢 0.77 2.16 1.07~4.10 0.024 注:扩张器额定容积结果为与<200 mL相比,扩张器置入部位结果为与头皮相比 -

下载:

下载: