Effects and mechanism of age on the stiffness and the fibrotic phenotype of fibroblasts of human hypertrophic scar

-

摘要:

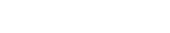

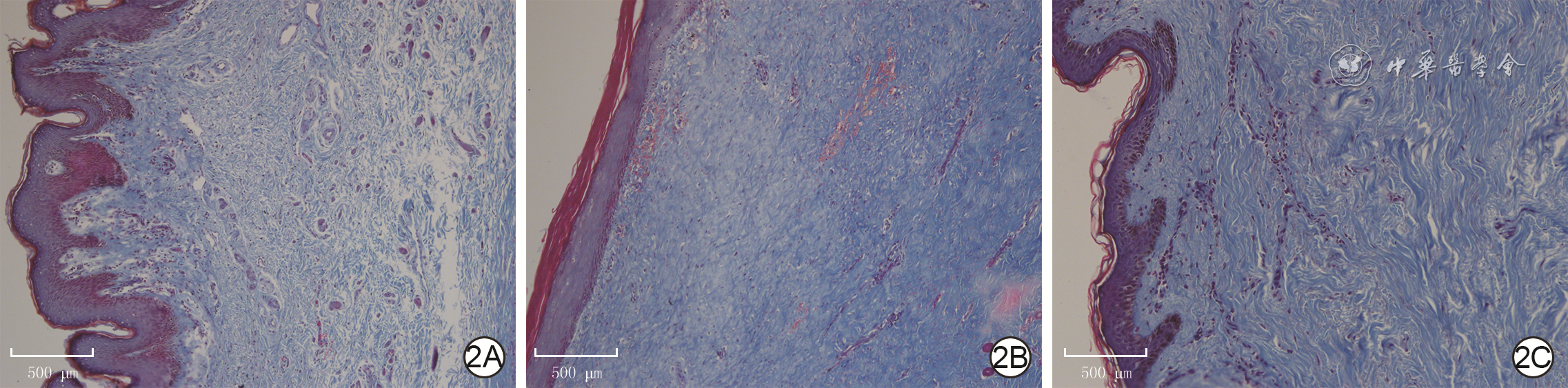

目的 探讨年龄对人增生性瘢痕硬度和成纤维细胞(Fb)纤维化表型的影响及其可能的分子机制。 方法 采用实验研究方法。收集2020年1—6月解放军总医院第四医学中心烧伤整形外科收治的10例瘢痕患者(男4例、女6例)手术切除的增生性瘢痕组织和10例患者(男5例、女5例,年龄7~41岁)手术后剩余的正常全层皮肤组织。根据患者年龄,将6例患者[(10.7±1.6)岁]瘢痕组织纳入年轻组,将4例患者[(40.0±2.2)岁]瘢痕组织纳入年长组。对正常皮肤和2组瘢痕组织,行苏木精-伊红(HE)染色观察组织形态,行Masson染色观察胶原形态、排列并测定胶原含量,冻干及金属镀膜后在扫描电子显微镜下观察真皮层胶原纤维微观形态。采用原子力显微镜在液相下测量2组瘢痕组织硬度。取2组瘢痕组织,分离和培养Fb,采用倒置相差显微镜观察其形态,并采用细胞免疫荧光法检测桩蛋白的表达以反映细胞形态,采用细胞免疫荧光法检测促纤维化蛋白α平滑肌肌动蛋白(α-SMA)、转化生长因子β1(TGF-β1)和Ⅰ型胶原表达及机械力转导相关蛋白Yes相关蛋白(YAP)和增殖相关蛋白Ki67的表达,采用实时荧光定量反转录PCR法检测促纤维化基因TGF-β1、α-SMA和Ⅰ型胶原,抑制纤维化基因TGF-β3及机械力转导相关基因Rho相关激酶1(ROCK1)和YAP mRNA表达。对数据行单因素方差分析、LSD-t检验。 结果 HE染色可见,正常皮肤表皮层凹凸不平,真皮层可见血管和汗腺等附属器;年轻组、年长组瘢痕组织表皮层均较为扁平,真皮层血管和汗腺等附属器罕见。Masson染色和扫描电子显微镜下可见,正常皮肤胶原纤维排列松散、无序,而2组瘢痕组织胶原纤维排列均较为致密、整齐,且年轻组瘢痕组织胶原纤维较年长组更为致密。年轻组、年长组瘢痕组织胶原含量明显高于正常皮肤组织(t=8.02、3.15,P<0.05或P<0.01),年长组瘢痕组织胶原含量明显低于年轻组(t=4.84,P<0.05)。年长组瘢痕组织真皮层硬度为(50.3±1.1)kPa,明显高于年轻组的(35.2±0.8)kPa(t=11.43,P<0.05)。2组瘢痕Fb在倒置相差显微镜下及经细胞免疫荧光法观察,在形态上无明显差异。年长组瘢痕Fb细胞质中Ⅰ型胶原和TGF-β1表达较年轻组明显升高,2组瘢痕Fb细胞质中α-SMA表达相近。年长组瘢痕Fb细胞质和细胞核中YAP表达较年轻组明显增多,2组瘢痕Fb细胞核中Ki67表达无明显差异。年长组瘢痕Fb中TGF-β1和Ⅰ型胶原mRNA表达量明显高于年轻组(t=2.87、4.85,P<0.05或P<0.01),TGF-β3 mRNA表达量明显低于年轻组(t=3.36,P<0.05),α-SMA mRNA表达量与年轻组无明显差异(t=1.14,P>0.05)。年长组瘢痕Fb中ROCK1和YAP mRNA表达量明显高于年轻组(t=2.98、7.60,P<0.05或P<0.01)。 结论 年长者皮肤损伤后更容易发生瘢痕愈合,其分子机制可能是由于创面愈合过程中会产生硬度较高的细胞外基质成分使得组织硬度增加,从而激活ROCK和YAP/转录共激活因子PDZ结合基序基因的表达,进而促进促纤维化基因和蛋白的表达。 Abstract:Objective To explore the effects and potential molecular mechanism of age on the stiffness and the fibrotic phenotype of fibroblasts (Fbs) of human hypertrophic scar. Methods The experimental research method was used. From January to June 2020, the surgically removed hypertrophic scar tissue of 10 scar patients (4 males and 6 females) and residual full-thickness normal skin tissue of 10 cases (5 males and 5 females, aged 7-41 years) were collected after operation in Department of Burns and Plastic Surgery of the Fourth Medical Center of the PLA General Hospital. The hypertrophic scar tissue of 6 patients aged (10.7±1.6) years was included into the young group and the hypertrophic scar tissue of 4 patients aged (40.0±2.2) years was included into the elderly group according to the age of patients. For the normal skin tissue and scar tissue in the two groups, hematoxylin eosin (HE) staining was performed to observe the tissue morphology, Masson staining was performed to observe the morphology and arrangement of collagen and quantify the content of collagen, and scanning electron microscope was used to observe the microscopic difference of dermal collagen fibers after the samples were freeze-dried and metal coated. The stiffness of scar tissue in the two groups was measured by atomic force microscope under the liquid phase. The scar tissue in the two groups was collected and the Fbs were isolated and cultured. The morphological differences of the Fbs were observed under the inverted phase contrast microscope, and the protein expression of paxillin was detected with cellular immunofluorescence to reflect the morphology of the Fbs. Cellular immunofluorescence was used to detect the expressions of pro-fibrosis protein α-smooth actin (α-SMA), transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), and type Ⅰ collagen, mechanotransduction-related protein Yes-associated protein (YAP), and the proliferation-related protein Ki67. Real-time fluorescent quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction was used to detect the mRNA expressions of pro-fibrosis genes of TGF-β1, α-SMA, and type Ⅰ collagen, fibrosis inhibiting gene of TGF-β3, and mechanotransduction-related genes of Rho-associated protein 1 (ROCK1) and YAP. Data were statistically analyzed with one-way analysis of variance and least significant difference t test. Results HE staining showed that the epidermal layer of normal skin was uneven, and blood vessels and sweat glands could be seen in the dermal layer; the epidermal layer of the scar tissue in the two groups was relatively flat, and blood vessels and sweat glands were rare. Masson staining and scanning electron microscopy showed that the collagen fibers in normal skin arranged loosely and disorderly, while the collagen fibers in scar tissue of the two groups arranged densely and orderly, and the collagen fibers in scar tissue of the young group were denser than those of the elderly group. The collagen content in scar tissue of the young group and the elderly group was significantly higher than that of the normal skin tissue (t=8.02, 3.15, P<0.05 or P<0.01), and the collagen content in scar tissue of the elderly group was significantly lower than that of the young group (t=4.84, P<0.05). The dermal stiffness of scar tissue in the elderly group was (50.3±1.1) kPa, significantly higher than (35.2±0.8) kPa in the young group (t=11.43, P<0.05). There were no obvious differences in the morphology of scar Fbs in the two groups observed under inverted phase contrast microscope and by cellular immunofluorescence. The expressions of type Ⅰ collagen and TGF-β1 in scar Fbs cytoplasm of the elderly group were significantly higher than those in the young group, while the expressions of α-SMA in scar Fbs cytoplasm were close in the two groups. The expressions of YAP in cytoplasm and nucleus of scar Fbs in the elderly group were significantly higher than those in the young group, while the expressions of Ki67 in scar Fbs nucleus of the two groups were close. The mRNA expressions of TGF-β1 and type Ⅰ collagen in scar Fbs of the elderly group were significantly higher than those in the young group (t=2.87, 4.85, P<0.05 or P<0.01), the mRNA expression of TGF-β3 in scar Fbs of the elderly group was significantly lower than that in the young group (t=3.36, P<0.05), and the mRNA expressions of α-SMA in scar Fbs of the two groups were close (t=1.14, P>0.05). The mRNA expressions of ROCK1 and YAP in scar Fbs of the elderly group were significantly higher than those in the young group (t=2.98, 7.60, P<0.05 or P<0.01). Conclusions The elderly are prone to scar healing after skin injury. The molecular mechanism may be attributed to the production of extracellular matrix components with higher stiffness, which increases tissue stiffness and thereby activates the expressions of ROCK and YAP/transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif genes, promoting pro-fibrosis gene and protein expression. -

Key words:

- Cicatrix /

- Hardness /

- Fibroblast /

- Age /

- Gene and protein of fibrosis /

- Gene and protein of mechanotransduction

-

(1)腓浅动脉穿支解剖位置较为恒定,均走行于肌间隔内,无须过多解剖游离,转移不受蒂部旋转角度限制,供区损伤小,是修复拇趾皮肤软组织缺损较为理想的供区,此前鲜见报道。

(2)术前于腓骨小头与外踝尖连线向胫侧平移2 cm周围行彩色多普勒超声定位腓浅动脉穿支,穿支定位更明确,操作难度、手术风险明显降低。

随着工业的飞速发展,外伤所致拇趾皮肤软组织缺损患者日益增多,以往多行残端修整或截趾,以牺牲趾体长度的代价来换取创面的简单闭合。但由于生活水平的提高,患者保留拇趾长度、恢复良好外观及功能的意愿愈发强烈,临床医师处理愈发棘手[1, 2]。本研究团队采用游离腓浅动脉穿支皮瓣修复拇趾皮肤软组织缺损,临床效果较佳。

1. 对象与方法

本回顾性观察性研究符合《赫尔辛基宣言》的基本原则。

1.1 入选标准

纳入标准:拇趾皮肤软组织缺损,采用游离腓浅动脉穿支皮瓣修复者;双侧小腿皮肤完整,且无外伤史及皮肤病史者。排除标准:随访时间不足6个月者,术中及随访资料不全者。

1.2 临床资料

2020年1月—2021年1月,苏州大学附属瑞华医院足踝外科收治13例拇趾皮肤软组织缺损患者,其中男12例、女1例;年龄16~53岁,平均41岁。致伤原因:重物砸伤者6例,叉车压伤者3例,皮带绞伤者1例,机器夹伤者2例,电锯伤者1例。患者伤后1~4 h,平均2.5 h急诊入院。入院后完善相关检查,均行急诊Ⅰ期清创,伴骨折行骨折复位内固定术者13例,伴血管、神经、肌腱损伤行探查修复术者2例,趾体离断行断趾再植术者5例,皮肤撕脱行撕脱皮肤回植术者6例。急诊术后皮肤软组织坏死部位:拇趾甲床者4例,拇趾背侧者4例,拇趾趾腹者3例,拇趾腓侧者1例,拇趾胫侧者1例。待坏死界限清晰后,行游离腓浅动脉穿支皮瓣修复。急诊手术至皮瓣修复时间为10~38 d,平均19.5 d。

1.3 治疗方法

1.3.1 术前穿支定位

术前于患趾同侧小腿,应用彩色多普勒超声诊断仪,沿腓骨小头至外踝尖连线向胫侧平移2 cm的线,由近及远寻找腓浅动脉穿支穿出点并于体表标记。测量腓骨小头与外踝尖连线长度(32~37 cm,平均34 cm)并标记中点。13例患者13个皮瓣供区共定位41条穿支,平均每个供区3.15条穿支。

1.3.2 麻醉方式

所有手术均采用脊椎麻醉+连续硬膜外麻醉。

1.3.3 受区准备

供受区均在气压止血带下进行手术。予体积分数3%过氧化氢、生理盐水、10 g/L苯扎溴铵冲洗创面,彻底切除坏死组织,刮除创面肉芽组织直至出现新鲜渗血,修剪距创缘0.2 cm的创周皮肤。部分患者见拇趾末节趾骨部分坏死,予摘除死骨。用生理盐水再次冲洗创面后,自创缘纵行切开皮肤,解剖受区血管,首选第一跖背动脉及趾背静脉为受区血管。放松止血带,观察血管喷血良好后标记备用。本组患者扩创后皮肤软组织缺损面积为4.5 cm×2.5 cm~12.0 cm×3.0 cm。

1.3.4 皮瓣设计

根据创面大小、形状设计样布。将腓骨小头至外踝尖连线向胫侧平移2 cm的线作为皮瓣轴心线,以轴心线中点附近术前彩色多普勒超声定位的穿支穿出点为中心,根据样布设计腓浅动脉穿支皮瓣,皮瓣面积较创面面积适当扩大。

1.3.5 皮瓣切取

沿设计线切开皮瓣前缘皮肤,于深筋膜浅层解剖寻找腓浅动脉穿支穿出点。确认穿支进入皮瓣后,根据穿支实际位置,适当调整皮瓣的切取位置。游离皮瓣周缘,于腓骨长肌和趾长伸肌间隔内,沿穿支走行向近端解剖分离,沿途结扎穿支发出的肌支,直至见到腓浅动脉主干及其伴行的腓浅神经并加以保护。解剖皮瓣蒂部时,常规切取部分深筋膜,避免裸化蒂部穿支。根据受区需要,解剖出足够长度的血管蒂,予结扎并切断。本组患者皮瓣切取面积为5.0 cm×3.0 cm~13.0 cm×4.0 cm。将皮瓣转移至受区,与创缘缝合数针固定。供区彻底止血后直接缝合。

1.3.6 血管吻合

显微镜下将皮瓣蒂部血管与受区动静脉进行端端吻合。本组患者中,皮瓣蒂部血管与第一跖背动脉及趾背静脉吻合者10例,与足底内侧动脉及跖底静脉吻合者1例,与拇趾腓侧趾固有动脉及趾背静脉吻合者2例。皮瓣表面做一小切口观察皮瓣血运,松止血带见皮瓣血运佳后,缝合创缘。用无菌敷料包扎,医用高分子夹板外固定。

1.3.7 术后处理

补充血容量;常规行抗炎、抗凝、抗痉挛治疗;患肢抬高,略高于心脏水平;60 W烤灯照射;皮瓣表面切口处用肝素浸润的棉球湿敷。

1.4 观测指标

术中记录穿支数目、类型及皮瓣切取时间,测量皮瓣穿支血管蒂长度及穿支直径。术后记录皮瓣成活情况、供受区愈合时间及愈合后情况。随访记录皮瓣的色泽、质地、弹性,患者站立、行走功能,供区恢复情况以及患者对供受区恢复情况的满意度。末次随访,采用英国医学研究会感觉功能评定标准[3]评定皮瓣感觉功能,分为5级:S0级为感觉完全丧失,S1级为存在深部痛觉,S2级为存在浅感觉及触觉且有较弱的两点辨别觉,S3级为存在浅感觉及触觉且有较强的两点辨别觉,S4级为感觉正常;采用美国足踝外科学会评分系统[4]对患肢功能进行综合评价,满分为100分,其中90~100分为优,75~89分为良,50~74分为可,<50分为差,另计算优良率。

2. 结果

术中共探及腓浅动脉穿支13条,均为肌间隔穿支;血管蒂长度2~5 cm,平均4 cm;穿支直径0.3~0.5 mm,平均0.4 mm。皮瓣切取时间11~26 min,平均17 min。本组13例患者术后皮瓣均完全成活,未发生血管危象。术后9~18 d,平均13.7 d,供受区创面均愈合良好。术后随访6~14个月,平均8个月,皮瓣色泽、质地、弹性良好;11例患者外形无明显臃肿,另外2例患者因皮下脂肪较厚,外观臃肿,Ⅱ期行皮瓣修薄整形;所有患者均恢复正常行走、站立功能;小腿供区仅遗留一条线状瘢痕,无明显瘢痕增生或色素沉着;所有患者对供受区恢复情况表示满意。末次随访,皮瓣感觉功能评定为S3级者2例、S2级者9例、S1级者2例;患肢功能评分为81~97分,平均89.8分,其中评定为优者7例、良者6例,优良率为100%。

典型病例:患者男,52岁,因重物砸伤致右足拇趾末节骨折伴趾尖动脉、神经断裂及皮肤软组织挫裂3 h入院。入院后急诊行骨折复位内固定及血管、神经修复。术后7 d右足拇趾末节甲床处皮肤发黑、血运不佳,继续予换药观察。待坏死界限清晰后,于入院后12 d切取游离腓浅动脉穿支皮瓣修复创面。术前作右小腿腓骨小头与外踝尖连线,并向胫侧平移2 cm,于该连线周围行彩色多普勒超声定位穿支穿出点,并于体表标记。术前测量的腓骨小头与外踝尖连线长度为32 cm,标记其中点。术中扩创后创面面积为7.5 cm×2.5 cm。同前设计及切取面积为8.0 cm×3.0 cm的腓浅动脉穿支皮瓣,皮瓣血管蒂长度为5 cm、穿支直径为0.4 mm。皮瓣切取时间为11 min。皮瓣切取后供区直接缝合。将皮瓣蒂部血管与受区第一跖背动脉及趾背静脉端端吻合。术后皮瓣存活良好,未出现血管危象。术后10 d,供受区创面愈合。术后8个月随访,皮瓣色泽、质地、弹性良好,外形无明显臃肿;患者恢复正常行走、站立功能;供区仅遗留一条线状瘢痕,无明显瘢痕增生或色素沉着;患者对术后供受区恢复情况表示满意;皮瓣感觉恢复至S2级;患肢功能评分为97分,评定为优。见图1。

3. 讨论

拇趾在足部生物力学中起着至关重要的作用,其不仅参与步态周期的发起[5],同时还承担着行走过程中足趾60%的负荷[2]。大部分截趾或残端修整操作会损伤第一跖趾关节,使足胫侧负重功能受损,负重区域向前足腓侧转移,导致转移性跖痛或外侧足趾畸形[6]。拇趾解剖学完整性遭到破坏,足部抓持力、蹬地力减弱,长此以往,会导致足底溃疡及胼胝体形成。目前针对拇趾皮肤软组织缺损的修复,常需保留趾体长度,恢复解剖学完整性,实现可靠而美观的皮瓣覆盖的同时,将供区并发症降至最低,这也是目前临床医师追求的目标[7]。保留拇趾长度,不仅有利于恢复拇趾及其周围结构的解剖学完整性,还可满足患者对足部美观的要求,避免造成不良的心理影响。

针对拇趾皮肤软组织缺损,皮瓣供区选择较多,但各有优劣。带蒂皮瓣[8, 9, 10]无须显微外科操作,临床应用较广泛。为尽可能降低供区损伤,多于足部非功能区切取皮瓣[11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16];部分学者选择皮神经营养血管皮瓣[17, 18, 19]以促进皮瓣感觉恢复。穿支皮瓣因较薄,不损伤供区主干血管,已被用于修复足部皮肤软组织缺损[20, 21, 22, 23]。随着显微外科技术的飞速发展,临床医师追求实现供瓣区美学缝合的同时,尽可能降低供区损伤[24, 25, 26, 27]。足部带蒂皮瓣虽与创面质地更为接近,但供受区位于同一部位,影响美观。皮瓣切取宽度有限,若切取面积较大,常需植皮修复,不美观亦不耐磨。小腿远端带蒂皮瓣虽无须进行显微吻合,但若皮瓣蒂部处理不当,易造成牵拉扭转,不利于皮瓣成活。

采用游离腓浅动脉穿支皮瓣修复拇趾皮肤软组织缺损,皮瓣血供丰富,穿支直径大部分为0.5 mm[28, 29, 30],与受区血管直径相近,供受区血管吻合后,皮瓣坏死鲜有发生[31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36]。本研究术中测量的穿支直径平均0.4 mm,术后皮瓣均顺利成活,未发生血管危象。腓浅动脉穿支皮瓣供区位于小腿外侧,手术体位摆放方便,且该部位皮肤薄且耐磨,颜色、质地与足部接近,术后一般无须进行皮瓣修薄整形,本组也仅有2例患者因外形臃肿行皮瓣修薄整形。腓浅动脉穿支皮瓣蒂部均为肌间隔穿支,解剖游离操作简单,不损伤供区主干血管和肌肉组织;皮瓣血管蒂长度充足,可根据受区需要较为自由进行断蒂;皮瓣切取宽度小于4.0 cm,供区均可直接闭合,避免了因植皮对供区外观及功能的影响。本组患者术中大多选择第一跖背动脉与皮瓣蒂部血管吻合,无须牺牲受区主干血管即可重建皮瓣血运。另外,皮瓣切取时,可携带部分小腿深筋膜或腓骨长肌,用于修复伴有肌腱、肌肉等组织缺损或形成空腔的复杂创面。

但本术式存在以下不足:(1)穿支血管细,解剖费时费力;受区吻合时,操作难度大,有时无法进行端端吻合,对术者穿支血管解剖分离及显微外科技术要求高;(2)腓浅神经上段仅为过路神经,没有发出皮支进入皮瓣内[37],无法与受区合适神经吻合。术后皮瓣未恢复保护性感觉前,应注意防护,避免发生烫伤、冻伤等二次损伤。但因本组患者皮瓣切取面积较小,随访观察到患者术后6个月均可恢复保护性感觉,2例患者感觉甚至可恢复至S3级。

本术式注意事项:(1)术前以腓骨小头与外踝尖连线向胫侧平移2 cm为皮瓣轴心线,于轴心线周围行彩色多普勒超声定位穿支穿出点并于体表标记。优先以皮瓣轴心线中点附近穿支穿出点为中心设计皮瓣,根据术中实际情况对皮瓣位置进行适当调整。(2)优先选择第一跖背动脉作为受区动脉;当第一跖背动脉细小或缺如时,选择趾底动脉或足背动脉分支为受区动脉。本组患者中有3例第一跖背动脉缺如,皮瓣蒂部血管与足底内侧动脉相吻合者1例,与拇趾腓侧趾固有动脉相吻合者2例。(3)术中解剖时,不提倡裸化穿支,应携带部分深筋膜,保护穿支血管的同时,还可保留深筋膜中丰富的血管网。(4)血管吻合应尽量行端端吻合。当受区血管直径为皮瓣蒂部血管直径的2倍及以内时,可对蒂部血管行“鱼嘴样”处理,扩大外径后再吻合;当受区血管直径为皮瓣蒂部血管直径的2倍以上时,可携带一段腓浅动脉主干来进行吻合或将受区血管直径缩小的同时对蒂部血管行“鱼嘴样”处理。(5)皮瓣切取时要注意保护腓浅神经,以免其损伤导致小腿外侧及足背感觉功能障碍。

综上所述,游离腓浅动脉穿支皮瓣血管解剖较为恒定,皮瓣薄且耐磨,色泽、质地良好,皮瓣切取后供区损伤小,可以最大限度保留拇趾外形及功能,是一种修复拇趾皮肤软组织缺损的有效方法。

所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突 -

参考文献

(36) [1] KirkwoodTB. Understanding the odd science of aging[J]. Cell, 2005,120(4):437-447.DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.027. [2] BakerDJ, PetersenRC. Cellular senescence in brain aging and neurodegenerative diseases: evidence and perspectives[J]. J Clin Invest, 2018,128(4):1208-1216. DOI: 10.1172/JCI95145. [3] RamirezT, LiYM, YinS, et al. Aging aggravates alcoholic liver injury and fibrosis in mice by downregulating sirtuin 1 expression[J]. J Hepatol, 2017,66(3):601-609. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.11.004. [4] ShusterS, BlackMM, Mc VitieE. The influence of age and sex on skin thickness, skin collagen and density[J]. Br J Dermatol, 1975,93(6):639-643. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1975.tb05113.x. [5] MooreAL, MarshallCD, BarnesLA, et al. Scarless wound healing: transitioning from fetal research to regenerative healing[J]. Wiley interdiscip Rev Dev Biol, 2018,7(2): 10.1002/wdev.309. DOI: 10.1002/wdev.309. [6] WillyardC. Unlocking the secrets of scar-free skin healing[J]. Nature, 2018,563(7732):S86-88. DOI: 10.1038/d41586-018-07430-w. [7] SolonJ, LeventalI, SenguptaK, et al. Fibroblast adaptation and stiffness matching to soft elastic substrates[J]. Biophys J, 2007,93(12):4453-4461. DOI: 10.1529/biophysj.106.101386. [8] WellsRG. Tissue mechanics and fibrosis[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2013,1832(7):884-890. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.02.007. [9] DasguptaI, McCollumD. Control of cellular responses to mechanical cues through YAP/TAZ regulation[J]. J Biol Chem, 2019,294(46):17693-17706. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.REV119.007963. [10] DupontS. Role of YAP/TAZ in cell-matrix adhesion-mediated signalling and mechanotransduction[J]. Exp Cell Res, 2016,343(1):42-53. DOI: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2015.10.034. [11] LichtmanMK, Otero-VinasM, FalangaV. Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) isoforms in wound healing and fibrosis[J]. Wound Repair Regen, 2016,24(2):215-222. DOI: 10.1111/wrr.12398. [12] LiuF, LagaresD, ChoiKM, et al. Mechanosignaling through YAP and TAZ drives fibroblast activation and fibrosis[J]. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, 2015,308(4):L344-357. DOI: 10.1152/ajplung.00300.2014. [13] SzetoSG, NarimatsuM, LuM, et al. YAP/TAZ are mechano- regulators of TGF-β-Smad signaling and renal fibrogenesis[J]. J Am Soc Nephrol, 2016,27(10):3117-3128.DOI: 10.1681/asn.2015050499. [14] AbramczykH, ImielaA, Brozek-PluskaB, et al. Advances in Raman imaging combined with AFM and fluorescence microscopy are beneficial for oncology and cancer research[J]. Nanomedicine (Lond), 2019,14(14):1873-1888. DOI: 10.2217/nnm-2018-0335. [15] BhushanB. Nanotribological and nanomechanical properties of skin with and without cream treatment using atomic force microscopy and nanoindentation[J]. J Colloid Interface Sci, 2012,367(1):1-33. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.10.019. [16] StylianouA, LekkaM, StylianopoulosT. AFM assessing of nanomechanical fingerprints for cancer early diagnosis and classification: from single cell to tissue level[J]. Nanoscale, 2018,10(45):20930-20945. DOI: 10.1039/c8nr06146g. [17] GauglitzGG, KortingHC, PavicicT, et al. Hypertrophic scarring and keloids: pathomechanisms and current and emerging treatment strategies[J]. Mol Med, 2011,17(1/2):113-125. DOI: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00153. [18] PuglieseE, CoentroJQ, RaghunathM, et al. Wound healing and scar wars[J]. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2018,129:1-3. DOI: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.05.010. [19] 张波, 王正国, 朱佩芳. 皮肤无瘢痕愈合机制的研究进展[J]. 中华烧伤杂志, 2002,18(5):318-320. [20] KöseO, WaseemA. Keloids and hypertrophic scars: are they two different sides of the same coin?[J]. Dermatol Surg, 2008,34(3):336-346. DOI: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2007.34067.x. [21] RittiéL, FisherGJ. Natural and sun-induced aging of human skin[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2015,5(1):a015370. DOI: 10.1101/cshperspect.a015370. [22] GeorgesPC, HuiJJ, GombosZ, et al. Increased stiffness of the rat liver precedes matrix deposition: implications for fibrosis[J]. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol, 2007,293(6):G1147-1154. DOI: 10.1152/ajpgi.00032.2007. [23] Viji BabuPK, RiannaC, BelgeG, et al. Mechanical and migratory properties of normal, scar, and Dupuytren's fibroblasts[J]. J Mol Recognit, 2018,31(9):e2719. DOI: 10.1002/jmr.2719. [24] TschumperlinDJ, LagaresD. Mechano-therapeutics: targeting mechanical signaling in fibrosis and tumor stroma[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2020,212:107575. DOI: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020.107575. [25] TschumperlinDJ, LigrestiG, HilscherMB, et al. Mechanosensing and fibrosis[J]. J Clin Invest, 2018,128(1):74-84. DOI: 10.1172/JCI93561. [26] WuH, YuY, HuangH, et al. Progressive pulmonary fibrosis is caused by elevated mechanical tension on alveolar stem cells[J]. Cell, 2020,180(1):107-121.e17. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.11.027. [27] YaoB, ZhuDZ, CuiXL, et al. Modeling human hypertrophic scars with 3D preformed cellular aggregates bioprinting[J]. Bioactive Materials, 2021,In press. DOI: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2021.09.004. [28] HinzB. Myofibroblasts[J]. Exp Eye Res, 2016,142:56-70. DOI: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.07.009. [29] HinzB, McCullochCA, CoelhoNM. Mechanical regulation of myofibroblast phenoconversion and collagen contraction[J]. Exp Cell Res, 2019,379(1):119-128.DOI: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.03.027. [30] KnipeRS, ProbstCK, LagaresD, et al. The Rho kinaseis oforms ROCK1 and ROCK2 each contribute to the development of experimental pulmonary fibrosis[J]. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol, 2018,58(4):471-481. DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0075OC. [31] ShiJ, SurmaM, YangY, et al. Disruption of both ROCK1 and ROCK2 genes in cardiomyocytes promotes autophagy and reduces cardiac fibrosis during aging[J]. FASEB J, 2019,33(6):7348-7362. DOI: 10.1096/fj.201802510R. [32] ZhouY, HuangX, HeckerL, et al. Inhibition of mechanosensitive signaling in myofibroblasts ameliorates experimental pulmonary fibrosis[J]. J Clin Invest, 2013,123(3):1096-1108. DOI: 10.1172/JCI66700. [33] NoguchiS, SaitoA, NagaseT. YAP/TAZ signaling as a molecular link between fibrosis and cancer[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2018,19(11):3674. DOI: 10.3390/ijms19113674. [34] Picollet-D'hahanN, DolegaME, LiguoriL, et al. A 3D toolbox to enhance physiological relevance of human tissue models[J]. Trends Biotechnol, 2016,34(9):757-769.DOI: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.06.012. [35] YanWC, DavoodiP, VijayavenkataramanS, et al. 3D bioprinting of skin tissue: from pre-processing to final product evaluation[J]. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2018,132:270-295.DOI: 10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.016. [36] 朱冬振, 王一惠, 王睿, 等. 外源性肿瘤坏死因子α对三维环境下小鼠间充质干细胞向汗腺细胞分化的影响及机制[J]. 中华烧伤杂志, 2020,36(3):187-194. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn501120-20200105-00005. -

表1 实时荧光定量反转录PCR检测2组患者瘢痕成纤维细胞中纤维化相关基因和机械力转导相关基因的表达

基因名称 引物序列(5’→3’) 产物大小(bp) GAPDH 上游:GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT 197 下游:GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG TGF-β1 上游:CAATTCCTGGCGATACCTCAG 86 下游:GCACAACTCCGGTGACATCAA TGF-β3 上游:ACTTGCACCACCTTGGACTTC 114 下游:GGTCATCACCGTTGGCTCA α-SMA 上游:GTGTTGCCCCTGAAGAGCAT 116 下游:GCTGGGACATTGAAAGTCTCA Ⅰ型胶原 上游:GAGGGCCAAGACGAAGACATC 140 下游:CAGATCACGTCATCGCACAAC YAP 上游:TAGCCCTGCGTAGCCAGTTA 177 下游:TCATGCTTAGTCCACTGTCTGT ROCK1 上游:AACATGCTGCTGGATAAATCTGG 93 下游:TGTATCACATCGTACCATGCCT 注:GAPDH为3-磷酸甘油醛脱氢酶,TGF为转化生长因子,α-SMA为α平滑肌肌动蛋白,YAP为Yes相关蛋白,ROCK1为Rho相关激酶1 期刊类型引用(4)

1. 侯国清,岳海龙,常倩,马俊涛. 右美托咪定通过转化生长因子-β1途径对大鼠脊柱切除术后硬膜外纤维化的影响. 实用临床医药杂志. 2025(01): 77-82 .  百度学术

百度学术2. 胡艳阁,丁伟,朱薇. 头皮刃厚皮回植治疗中厚皮供区创面的临床研究. 皖南医学院学报. 2023(01): 40-42 .  百度学术

百度学术3. 孙佳辰,孙天骏,申传安,赵虹晴,刘馨竹,张熠杰. 衰老皮肤中ⅩⅦ型胶原蛋白α1对表皮干细胞的影响及微小RNA干预机制. 中华烧伤与创面修复杂志. 2022(09): 839-848 .  本站查看

本站查看4. 肖臻阳,林志琥,汪明柱,徐家钦,刘钰,熊武,张熙,周建大. 遵循平衡法则 提高创面修复临床与科研水平. 中国医师杂志. 2021(12): 1761-1763 .  百度学术

百度学术其他类型引用(2)

-

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载:

百度学术

百度学术