Significance of early lymphocyte-platelets ratio on the prognosis of patients with extensive burns

-

摘要:

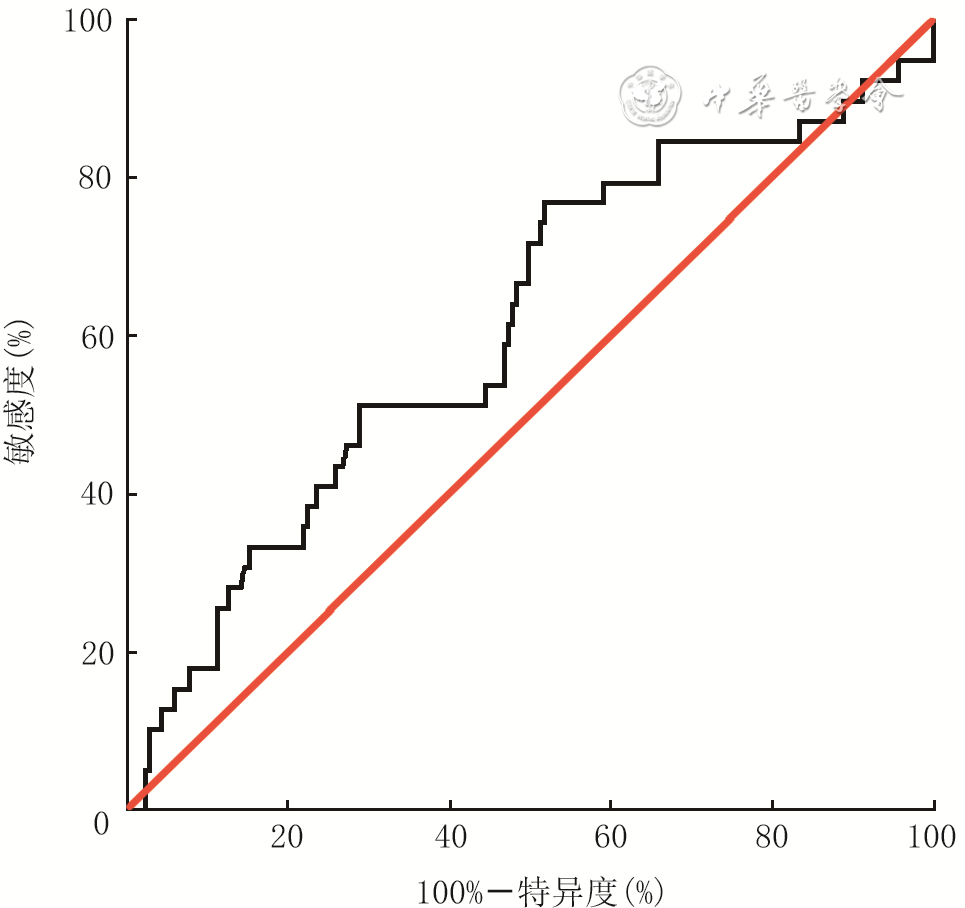

目的 分析大面积烧伤患者早期淋巴细胞/血小板比值(LPR)的变化趋势及特点,探讨LPR对患者预后的意义。 方法 采用回顾性病例系列研究方法。2008年1月—2018年12月,海军军医大学第一附属医院收治符合入选标准的大面积烧伤患者244例,其中男181例、女63例,年龄(44±16)岁,烧伤总面积为60.0%(42.0%,85.0%)体表总面积。收集患者入院后第1、2、3天血小板和淋巴细胞的检测结果并计算LPR,分析患者入院3 d内LPR的变化趋势。对患者年龄、性别、烧伤总面积、Ⅲ度及以上烧伤面积、合并吸入性损伤、LPR进行单因素、多因素logistic回归分析,筛选患者死亡的危险因素或独立危险因素。根据患者入院后第1天的LPR绘制受试者操作特征(ROC)曲线,找到LPR的最佳临界值并以此将患者分为高LPR组(136例)和低LPR组(108例),比较2组患者烧伤总面积、Ⅲ度及以上烧伤面积,合并吸入性损伤发生率、气管切开发生率、28 d内脱机时间、病死率等临床资料的差异。采用Kaplan-Meier法绘制生存曲线,预测2组患者入院90 d内存活率差异。对数据行Student t检验、Mann-Whitney U检验或 χ 2检验。 结果 入院3 d内,患者的LPR基本呈时间依赖性上升趋势。入院后第2、3天患者的LPR分别为8.6(5.3,14.4)、8.6(4.9,13.7),均明显高于入院后第1天的6.3(4.2,9.8), Z值分别为-4.25、-3.43, P<0.01。单因素logistic回归分析显示,年龄、烧伤总面积、Ⅲ度及以上烧伤面积、合并吸入性损伤、LPR均为影响患者死亡的危险因素(比值比分别为1.03、1.73、1.31、4.74、3.11,95%置信区间分别为1.01~1.06、1.40~2.13、1.21~1.42、1.62~13.86、1.41~6.88, P<0.01);多因素logistic回归分析显示,年龄、Ⅲ度及以上烧伤面积、LPR均为患者死亡的独立危险因素(比值比分别为1.06、1.36、2.85,95%置信区间分别为1.03~1.09、1.19~1.55、1.02~7.97, P<0.05或 P<0.01)。入院后第1天LPR预测患者死亡的ROC曲线下面积为0.61(95%置信区间为0.51~0.71, P<0.05),最佳临界值为5.8,对应的敏感度为77%,特异度为52%。高LPR组患者烧伤总面积、Ⅲ度及以上烧伤面积、合并吸入性损伤发生率、气管切开发生率、病死率均明显高于低LPR组( Z值分别为-3.06、-3.19, χ 2值分别为5.42、11.64、8.45, P<0.05或 P<0.01);高LPR组患者的28 d内脱机时间明显短于低LPR组( Z=-2.98, P<0.01)。Kaplan-Meier生存分析显示,低LPR组患者入院90 d内的存活率显著高于高LPR组( χ 2=8.24, P<0.01)。 结论 大面积烧伤患者早期LPR呈时间依赖性上升趋势。患者入院后第1天的LPR与烧伤总面积、Ⅲ度及以上烧伤面积、合并吸入性损伤、气管切开及患者病死率密切相关,且为评估大面积烧伤患者预后的独立危险因素之一。入院后第1天的LPR与患者入院90 d内的存活率存在明显相关性,可作为大面积烧伤危重程度的评估指标。 Abstract:Objective To analyze the changing trend and characteristics of lymphocyte-platelets ratio (LPR) of early stage in patients with extensive burns, and to explore the prognostic significance of LPR. Methods A retrospective case series study was conducted. From January 2008 to December 2018, 244 patients with extensive burns were admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Naval Medical University, including 181 males and 63 females, aged (44±16) years. The total burned area of patients was 60.0% (42.0%, 85.0%) total body surface area. Platelet and lymphocyte test results of patients were collected on the 1 st, 2 nd and 3 rd day after admission, and LPR of patients was calculated to analyze the changing trend of the three days after admission. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis were conducted to investigate the risk factors or independent risk factors for death of patients, including age, sex, total burn area, area of full-thickness burns and above, inhalation injury, and LPR. According to the 1 st day's LPR after admission of patients, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve predicting death of patients was drawn to find the optimal value of LPR. Patients were divided into high LPR group ( n=136) and low LPR group ( n=108) based on the optimal value of LPR, and the clinical data of total burn area, area of full-thickness burns and above, inhalation injury, tracheotomy, offline time of patients within 28 days, and mortality in the 2 groups were compared. The surviving curve of patients was drawn by Kaplan-Meier method to predict the difference of the 90-day survival rate between the two groups of patients. Data were statistically analyzed with Student's t test, Mann-Whitney U test, and chi-square test. Results Within 3 days of admission, the LPR of patients showed a time-dependent upward trend. LPR of patients on the 2 nd and 3 rd day after admission was 8.6 (5.3, 14.4) and 8.6 (4.9, 13.7), respectively, which were significantly higher than the 1 st day's 6.3 (4.2, 9.8), with Z values of -4.25 and -3.43, respectively, P<0.01. Univariate logistic regression analysis showed that age, total burn area, area of full-thickness burns and above, inhalation injury, and LPR were all risk factors for death of patients (with odds ratios of 1.03, 1.73, 1.31, 4.74, and 3.11, respectively, 95% confidence intervals of 1.01-1.06, 1.40-2.13, 1.21-1.42, 1.62-13.86, and 1.41-6.88, respectively, P<0.01). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed that age, area of full-thickness burns and above, and LPR were independent risk factors for death of patients (with odds ratios of 1.06, 1.36, and 2.85, respectively, 95% confidence intervals of 1.03-1.09, 1.19-1.55, 1.02-7.97, P<0.05 or P<0.01). The area under ROC curve of the 1 st day's LPR, predicting death of patients, was 0.61 (with 95% confidence interval of 0.51-0.71, P<0.05), and the optimal predicted value was 5.8 with corresponding sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 52% respectively. The total burn area, area of full-thickness burns and above, rates of incidence of inhalation injury, tracheotomy, and mortality of patients in high LPR group were significantly higher than those in low LPR group (with Z values of -3.06 and -3.19, χ 2 values of 5.42, 11.64, and 8.45, respectively, P<0.05 or P<0.01). The offline time of patients within 28 days in high LPR group was significantly shorter than that in low LPR group ( Z=-2.98, P<0.01). Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed that the 90-day survival rate of admission of patients in low LPR group was significantly higher than that of patients in high LPR group ( χ 2=8.24, P<0.01). Conclusions The early LPR of patients with extensive burns showed a time-dependent upward trend. The LPR on the first day after admission that is closely correlated with total burn area, area of full-thickness and deeper burns, inhalation injury, tracheotomy, and mortality of patients, is an independent risk factor for the prognosis of patients with extensive burns. The first day's LPR after admission is significantly correlated with the 90-day survival rate of patients, which can be used as an evaluation index for the severity of extensive burns. -

Key words:

- Burns /

- Risk factors /

- Prognosis /

- Early stage /

- Stress /

- Lymphocyte-platelets ratio /

- Systemic inflammatory response syndrome

-

参考文献

(27) [1] 罗鹏飞, 王光毅, 夏照帆. 严重烧伤脏器并发症的内源性细胞损伤机制研究进展[J]. 中华烧伤杂志, 2012, 28(3): 183-185. DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1009-2587.2012.03.006. [2] BoldeanuL, BoldeanuMV, BogdanM, et al. Immunological approaches and therapy in burns (Review)[J]. Exp Ther Med, 2020,20(3):2361-2367. DOI: 10.3892/etm.2020.8932. [3] ZhengCF, LiuWY, ZengFF, et al. Prognostic value of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratios among critically ill patients with acute kidney injury[J]. Crit Care, 2017,21(1):238. DOI: 10.1186/s13054-017-1821-z. [4] FengJR, QiuX, WangF, et al. Diagnostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in crohn's disease[J]. Gastroenterol Res Pract, 2017,2017:3526460. DOI: 10.1155/2017/3526460. [5] WangX, XieZ, LiuX, et al. Association of Platelet to lymphocyte ratio with non-culprit atherosclerotic plaque vulnerability in patients with acute coronary syndrome: an optical coherence tomography study[J]. BMC Cardiovasc Disord, 2017,17(1):175. DOI: 10.1186/s12872-017-0618-y. [6] LiXT, FangH, LiD, et al. Association of platelet to lymphocyte ratio with in-hospital major adverse cardiovascular events and the severity of coronary artery disease assessed by the Gensini score in patients with acute myocardial infarction[J]. Chin Med J (Engl), 2020,133(4):415-423. DOI: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000650. [7] ZhaoZ, LiuJ, WangJ, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) are associated with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection[J]. Int Immunopharmacol, 2017,51:1-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.intimp.2017.07.007. [8] TangC, ChengX, YuS, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte-to-white blood cell ratio predict the efficacy of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and the prognosis of locally advanced gastric cancer patients treated with the oxaliplatin and capecitabine regimen[J]. Onco Targets Ther, 2018,11:7061-7075. DOI: 10.2147/OTT.S176768. [9] QinS, LuY, ChenS, et al. The relationship of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio or platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and pancreatic cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes[J]. Clin Lab, 2019,65(7):1203-1209.DOI: 10.7754/Clin.Lab.2019.181226. [10] 王书侠, 张家明, 姚孝明, 等. 木犀草素对活化的 RAW 264.7巨噬细胞分泌炎症因子的影响[J].医学研究生学报,2017,30(1):31-35. DOI: 10.16571/j.cnki.1008-8199.2017.01.007. [11] 刘欣伟, 柳云恩, 王宇. Bruton酪氨酸蛋白激酶在创伤性休克诱发的全身炎症反应中研究与思考[J].创伤与急危重病医学,2017,5(3):145-147. DOI: 10.16048/j.issn.2095-5561.2017.03.05. [12] ZhangM, YangL, DuG, et al. Early diagnosis of infection occurs in burned patients and verification in vitro[J]. Int J Lab Hematol, 2018,40(4):448-452. DOI: 10.1111/ijlh.12810. [13] MarckRE, van der BijlI, KorstenH, et al. Activation, function and content of platelets in burn patients[J]. Platelets, 2019,30(3):396-402. DOI: 10.1080/09537104.2018.1448379. [14] WuRX, ChiuCC, LinTC, et al. Procalcitonin as a diagnostic biomarker for septic shock and bloodstream infection in burn patients from the Formosa Fun Coast dust explosion[J]. J Microbiol Immunol Infect, 2017,50(6):872-878. DOI: 10.1016/j.jmii.2016.08.021. [15] LiB, ZhouP, LiuY, et al. Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio in advanced Cancer: review and meta-analysis[J]. Clin Chim Acta, 2018,483:48-56. DOI: 10.1016/j.cca.2018.04.023. [16] ZamoraC, CantóE, NietoJC, et al. Binding of platelets to lymphocytes: a potential anti-inflammatory therapy in rheumatoid arthritis[J]. J Immunol, 2017,198(8):3099-3108. DOI: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601708. [17] RogovskiiVS. The linkage between inflammation and immune tolerance: interfering with inflammation in cancer[J]. Curr Cancer Drug Targets, 2017,17(4):325-332. DOI: 10.2174/1568009617666170109110816. [18] 陈秋杉, 王兴勇. 血小板在脓毒症各器官功能障碍中作用机制的研究进展[J].临床医学研究与实践,2020,5(17):197-198. DOI: 10.19347/j.cnki.2096-1413.202017073. [19] 梁华平, 王正国, 朱佩芳. 创伤后淋巴细胞的活化与全身炎症反应综合征[J].创伤外科杂志,2001,3(3):228-230. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1009-4237.2001.03.028. [20] DokterJ, MeijsJ, OenIM, et al. External validation of the revised Baux score for the prediction of mortality in patients with acute burn injury[J]. J Trauma Acute Care Surg, 2014,76(3):840-845. DOI: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000124. [21] 牛利斌, 王甲汉, 黄磊, 等. 影响大面积烧伤患者预后的相关因素分析[J].广东医学,2012,33(13):1936-1938. DOI: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-9448.2012.13.031. [22] 郭光华,朱峰,黄跃生,等. 吸入性损伤临床诊疗全国专家共识(2018版)[J/CD].中华损伤与修复杂志:电子版,2018,13(6):410-415. DOI: 10.3877/cma.j.issn.1673-9450.2018.06.003. [23] 邓献. 烧伤吸入性损伤的诊治研究进展[J].基层医学论坛,2019,23(19):2798-2799. DOI: 10.19435/j.1672-1721.2019.19.085. [24] LuG, WangJ. Dynamic changes in routine blood parameters of a severe COVID-19 case[J]. Clin Chim Acta, 2020,508:98-102. DOI: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.04.034. [25] FuJ, KongJ, WangW, et al. The clinical implication of dynamic neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and D-dimer in COVID-19: a retrospective study in Suzhou China[J]. Thromb Res, 2020,192:3-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.006. [26] GoltzmanG, PerlS, CohenL, et al. Single admission C-reactive protein levels as a sole predictor of patient flow and clinical course in a general internal medicine department[J]. Isr Med Assoc J, 2019,21(10):686-691. [27] HwangSY, ShinTG, JoIJ, et al. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker in critically-ill septic patients[J]. Am J Emerg Med,2017,35(2): 234-239.DOI: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.10.055. -

表1 影响244例大面积烧伤患者死亡的单因素logistic回归分析结果

因素 β值 Wald值 比值比 95%置信区间 P值 年龄(岁) 0.03 8.54 1.03 1.01~1.06 0.003 性别 0.44 1.35 1.55 0.74~3.24 0.245 烧伤总面积 (%TBSA) 0.55 26.59 1.73 1.40~2.13 <0.001 Ⅲ度及以上烧伤面积(%TBSA) 0.27 45.74 1.31 1.21~1.42 <0.001 合并吸入性损伤 1.56 8.06 4.74 1.62~13.86 0.005 入院后第1天LPR 1.14 7.86 3.11 1.41~6.88 0.005 注:TBSA为体表总面积,LPR为淋巴细胞/血小板比值 表2 影响244例大面积烧伤患者死亡的多因素logistic回归分析结果

因素 β值 Wald值 比值比 95%置信区间 P值 年龄(岁) 0.06 12.86 1.06 1.03~1.09 <0.001 性别 0.41 0.62 1.50 0.55~4.11 0.429 烧伤总面积(%TBSA) 0.02 0.01 1.02 0.73~1.42 0.906 Ⅲ度及以上烧伤面积(%TBSA) 0.30 20.58 1.36 1.19~1.55 <0.001 合并吸入性损伤 0.61 0.82 1.84 0.50~6.81 0.364 入院后第1天LPR 1.05 3.98 2.85 1.02~7.97 0.046 注:TBSA为体表总面积,LPR为淋巴细胞/血小板比值 表3 2组大面积烧伤患者临床资料比较

组别 例数 年龄(岁) 性别[例(%)] 烧伤总面积 [%TBSA, M( Q 1, Q 3)] Ⅲ度及以上烧伤面积[%TBSA, M( Q 1, Q 3)] 合并吸入性损伤[例(%)] 气管切开[例(%)] 男 女 低LPR组 108 45±15 82(75.9) 26(24.1) 50.0(40.0,75.0) 19.0(5.3,38.3) 66(61.1) 39(36.1) 高LPR组 136 43±16 99(72.8) 37(27.2) 70.0(45.0,88.0) 30.0(11.0,54.9) 102(75.0) 79(58.1) 统计量值 t=1.15 χ 2=0.31 Z=-3.06 Z=-3.19 χ 2=5.42 χ 2=11.64 P值 0.251 0.579 0.002 0.001 0.020 0.001 注:LPR为淋巴细胞/血小板比值,TBSA为体表总面积,ICU为重症监护病房;高LPR组患者的LPR≥5.8,低LPR组的LPR<5.8;脱机指脱离呼吸机 -

下载:

下载: