Changes of heparin-binding protein in severe burn patients during shock stage and its effects on human umbilical vein endothelial cells and neutrophils

-

摘要:

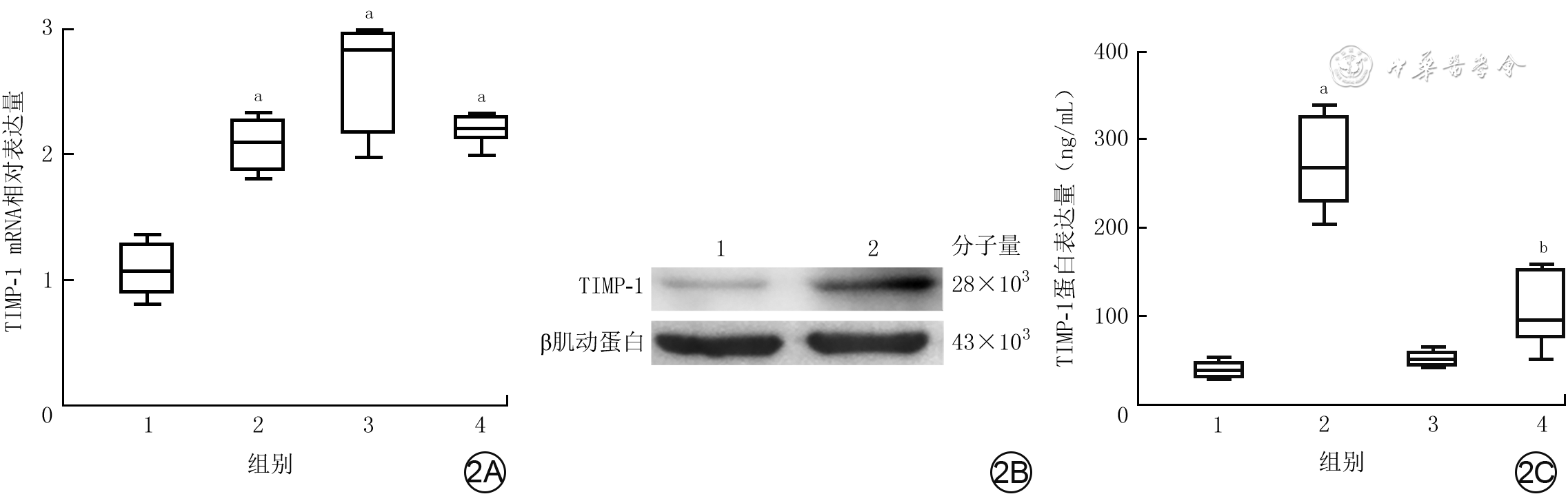

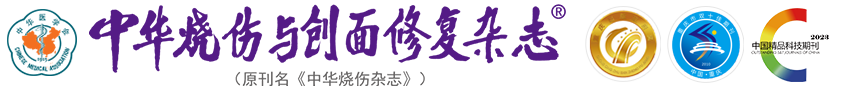

目的 探讨严重烧伤患者休克期肝素结合蛋白(HBP)的变化及其在体外对人脐静脉血管内皮细胞(HUVEC)和中性粒细胞的影响。 方法 采用前瞻性观察性研究与实验研究方法。将2020年8—11月南京医科大学附属苏州医院烧伤整形科收治的符合入选标准的20例严重烧伤患者纳入严重烧伤组[男12例、女8例,年龄为44.5(31.0,58.0)岁],同期招募该单位体检中心体检结果正常的20名健康志愿者纳入健康对照组[男13例、女7例,年龄为39.5(26.0,53.0)岁]。采用酶联免疫吸附测定(ELISA)法检测健康对照组志愿者血浆与严重烧伤组患者伤后48 h内血浆中HBP和组织金属蛋白酶抑制物1(TIMP-1)蛋白表达水平,分别对2组血浆中HBP和TIMP-1蛋白表达的相关性进行Pearson相关分析。取第4代对数生长期HUVEC进行实验,将细胞按随机数字表法(分组方法下同)分为常规培养的正常对照组(处理下同)与进行相应处理的重组HBP(rHBP)处理12 h组、rHBP处理24 h组、rHBP处理48 h组,采用实时荧光定量反转录PCR法检测细胞中TIMP-1的mRNA表达;将细胞分为正常对照组与进行相应处理的rHBP处理48 h组,采用蛋白质印迹法检测细胞中TIMP-1蛋白表达;将细胞分为正常对照组与加入相应试剂处理的单纯rHBP组、单纯抑蛋白酶多肽组、rHBP+抑蛋白酶多肽组(rHBP终物质的量浓度为200 nmol/L,抑蛋白酶多肽终质量浓度为20 μg/mL),培养48 h,采用ELISA法检测细胞培养上清液中TIMP-1蛋白表达水平。采用免疫磁珠分选法从前述10名健康志愿者外周静脉血中分离中性粒细胞,将细胞分为正常对照组与加入相应试剂处理的单纯重组TIMP-1(rTIMP-1)组、单纯佛波酯组、rTIMP-1+佛波酯组(rTIMP-1终质量浓度为500 ng/mL,佛波酯终物质的量浓度为10 nmol/L),培养1 h,采用免疫荧光法观测细胞中CD63蛋白表达,采用流式细胞术检测细胞中CD63蛋白阳性表达率,采用ELISA法检测细胞培养上清液中HBP和髓过氧化物酶(MPO)蛋白表达水平。正常对照组均于适宜时间点进行前述相关检测,细胞实验中各组样本数均为3。对数据行χ2检验、Mann-Whitney U检验、Kruskal-Wallis H检验、Tamhane T2检验。 结果 严重烧伤组患者血浆中HBP、TIMP-1蛋白表达水平分别为404.9(283.1,653.2)、262.1(240.6,317.4)ng/mL,均明显高于健康对照组志愿者的61.6(45.0,68.9)、81.0(66.3,90.0)ng/mL(Z值分别为-5.41、-5.21,P<0.01)。健康对照组志愿者血浆中HBP和TIMP-1蛋白表达相关性不强(P>0.05),严重烧伤组患者血浆中HBP和TIMP-1蛋白表达呈明显正相关(r=0.64,P<0.01)。与正常对照组比较,rHBP处理12 h组、rHBP处理24 h组、rHBP处理48 h组HUVEC中TIMP-1 mRNA表达水平均显著升高(t值分别为-3.58、-2.25、-1.26,P<0.05)。蛋白质印迹法检测显示,与正常对照组比较,rHBP处理48 h组HUVEC中TIMP-1蛋白表达明显增强。培养48 h,与正常对照组比较,单纯rHBP组HUVEC培养上清液中TIMP-1蛋白表达水平显著升高(t=9.43,P<0.05),单纯抑蛋白酶多肽组、rHBP+抑蛋白酶多肽组HUVEC培养上清液中TIMP-1蛋白表达水平均无明显变化(P>0.05);与单纯rHBP组比较,rHBP+抑蛋白酶多肽组HUVEC培养上清液中TIMP-1蛋白表达水平显著下降(t=4.76,P<0.01)。培养1 h,免疫荧光法和流式细胞术检测的各组中性粒细胞CD63蛋白表达结果趋势一致。培养1 h,与正常对照组比较,单纯rTIMP-1组中性粒细胞中CD63蛋白阳性表达率及细胞培养上清液中HBP、MPO蛋白表达水平均无明显变化(P>0.05),单纯佛波酯组、rTIMP-1+佛波酯组中性粒细胞中CD63蛋白阳性表达率及细胞培养上清液中HBP、MPO蛋白表达水平均明显升高(t值分别为2.41、3.82,5.73、1.05、4.16、1.08,P<0.05或P<0.01);与单纯佛波酯组比较,rTIMP-1+佛波酯组中性粒细胞中CD63蛋白阳性表达率及细胞培养上清液中HBP、MPO蛋白表达水平均明显下降(t值分别为5.26、2.83、1.26,P<0.05或P<0.01)。 结论 严重烧伤患者休克期血浆中HBP表达水平增加;HBP可在体外诱导HUVEC分泌TIMP-1,TIMP-1可降低人中性粒细胞CD63分子表达。 Abstract:Objective To investigate the changes of heparin-binding protein (HBP) in severe burn patients during shock stage and its effects on human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) and neutrophils in vitro. Methods Prospective observational and experimental research methods were used. Twenty severe burn patients who met the inclusion criteria and were admitted to the Department of Burns and Plastic Surgery of Affiliated Suzhou Hospital of Nanjing Medical University from August to November 2020 were included in severe burn group (12 males and 8 females, aged 44.5 (31.0, 58.0) years). During the same period, 20 healthy volunteers with normal physical examination results in the unit's Physical Examination Center were recruited into healthy control group (13 males and 7 females, aged 39.5 (26.0, 53.0) years). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method was used to detect the protein expression levels of HBP and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP-1) in plasma of patients within 48 hours after injury in severe burn group and in plasma of volunteers in healthy control group. The correlation between protein expression of HBP and that of TIMP-1 in the plasma in the two groups was analyzed by Pearson correlation analysis. The fourth passage of HUVECs in logarithmic growth phase were used for the experiment. The HUVECs were divided into normal control group with routine culture (the same treatment below) and recombinant HBP (rHBP)-treated 12 h group, rHBP-treated 24 h group, and rHBP-treated 48 h group with corresponding treatment according to the random number table (the same grouping method below), and the mRNA expression of TIMP-1 in cells was detected by real-time fluorescence quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. The HUVECs were divided into normal control group and rHBP-treated 48 h group with corresponding treatment, and the protein expression of TIMP-1 in the cells was detected by Western blotting. The HUVECs were divided into normal control group, rHBP alone group, aprotinin alone group, and rHBP+aprotinin group treated with the corresponding reagents (with the final molarity of rHBP being 200 nmol/L and the final concentration of aprotinin being 20 μg/mL, respectively), cultured for 48 h, and ELISA was used to detect the protein expression of TIMP-1 in the culture supernatant of cells. The neutrophils were isolated from the peripheral venous blood of the aforementioned 10 healthy volunteers by immunomagnetic bead sorting, and the cells were divided into normal control group, recombinant TIMP-1 (rTIMP-1) alone group, phorbol acetate (PMA) alone group, and rTIMP-1+PMA group treated with corresponding reagents (with the final concentration of rTIMP-1 being 500 ng/mL and the final molarity of PMA being 10 nmol/L, respectively). After being cultured for 1 h, the expression of CD63 protein in cells was detected by immunofluorescence method, the positive expression rate of CD63 protein in cells was detected by flow cytometry, and the protein expression levels of HBP and myeloperoxidase (MPO) in the culture supernatant of cells were detected by ELISA. The normal control group underwent the above-mentioned related tests at appropriate time points. The number of samples was 3 in each group of cell experiment. Data were statistically analyzed with chi-square test, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis H test, and Tamhane's T2 test. Results The protein expression levels of HBP and TIMP-1 in the plasma of patients in severe burn group were 404.9 (283.1, 653.2) and 262.1 (240.6, 317.4) ng/mL, respectively, which were both significantly higher than 61.6 (45.0, 68.9) and 81.0 (66.3, 90.0) ng/mL of volunteers in healthy control group (with Z values of -5.41 and -5.21, respectively, P<0.01). The correlation between the protein expression of HBP and that of TIMP-1 in the plasma of volunteers in healthy control group was not strong (P>0.05). The protein expression of HBP was significantly positively correlated with that of TIMP-1 in the plasma of patients in severe burn group (r=0.64, P<0.01). Compared with that in normal control group, the mRNA expression of TIMP-1 in HUVECs was significantly increased in rHBP-treated 12 h group, rHBP-treated 24 h group, and rHBP-treated 48 h group (with t values of -3.58, -2.25, and -1.26, respectively, P<0.05). Western blotting detection showed that compared with that in normal control group, the protein expression of TIMP-1 in HUVECs in rHBP-treated 48 h group was significantly enhanced. After 48 h of culture, compared with that in normal control group, the protein expression level of TIMP-1 in the culture supernatant of HUVECs in rHBP alone group was significantly increased (t=9.43, P<0.05), while the protein expression level of TIMP-1 in the culture supernatant of HUVECs didn't change significantly in aprotinin alone group or rHBP+aprotinin group (P>0.05); compared with that in rHBP alone group, the protein expression level of TIMP-1 in the culture supernatant of HUVECs in rHBP+aprotinin group was significantly decreased (t=4.76, P<0.01). After 1 h of culture, the trend of CD63 protein expression in neutrophils detected by immunofluorescence method and that by flow cytometry were consistent in each group. After 1 h of culture, compared with that in normal control group, the positive expression rate of CD63 protein in the neutrophils and the protein expression levels of HBP and MPO in the culture supernatant of cells in rTIMP-1 alone group all had no significant changes (P>0.05), while the positive expression rate of CD63 protein in the neutrophils and the protein expression levels of HBP and MPO in the culture supernatant of cells were all significantly increased in PMA alone group and rTIMP-1+PMA group (with t values of 2.41, 3.82, 5.73, 1.05, 4.16, and 1.08, respectively, P<0.05 or P<0.01); compared with that in PMA alone group, the positive expression rate of CD63 protein in the neutrophils and the protein expression levels of HBP and MPO in the culture supernatant of cells in rTIMP-1+PMA group were all significantly decreased (with t values of 5.26, 2.83, and 1.26, respectively, P<0.05 or P<0.01). Conclusions The expression level of HBP in the plasma of severe burn patients is increased during shock stage. HBP can induce HUVECs to secrete TIMP-1 in vitro, and TIMP-1 can reduce the expression of CD63 molecule in human neutrophils. -

结核病是全世界十大死亡病因之一[1]。我国报告的肺外结核占结核病总数的5%[2]。在肺外结核中,约50%以上患者伴病灶周围软组织的损害,这些损害最终破溃形成“结核性创面”[3]。结核性创面具有多变的临床表现,仍是发展中国家常见的皮肤病之一[4]。结核性创面发病早期因临床表现缺乏特异性,因此该类患者常延迟就诊[5];加之创面细菌培养阳性率低,造成了较高的漏诊率及误诊率[6];创面常伴潜行的皮下隧道,对治疗造成了一定的困难[3]。目前结核性创面的发病机制尚不清楚,同时缺乏特效的治疗手段[7, 8],与目前没有成熟的动物模型有关。因此,对动物模型的研究显得尤为重要。为了给深入研究结核性创面提供稳定可行的动物模型,本课题组使用牛分枝杆菌减毒株(BCG)对SD大鼠进行了结核性创面模型的构建并取得初步结果。

1. 材料与方法

本实验研究遵循山西医科大学和国家有关实验动物管理和使用的相关规定。

1.1 动物及主要试剂与仪器来源

15只健康无特殊病原体(SPF)级6周龄雄性SD大鼠,体重(200±20)g,由山西医科大学实验动物中心提供,许可证号:SCXK(晋)2015-0001。BCG购于美国ATCC菌株保存中心,Middlebrook OADC增菌液、Middlebrook 7H9培养基购于美国BD公司,弗氏完全佐剂购于美国Sigma公司,石碳酸品红染液、亚甲蓝复染液、苏木精染液购于北京索莱宝生物科技有限公司,伊红购于西亚化学科技(山东)有限公司。EclipseCi-L型光学显微镜购于日本尼康仪器有限公司。

1.2 BCG菌液培养

将-80 ℃冻存的BCG置于冰上,在室温中消融。在生物安全柜中将BCG加入预先添加OADC增菌液的7H9培养液中,置于37 ℃恒温摇床(转速80次/min)培养至菌落形成,通过测菌液吸光度值[9]的方法计数细菌浓度,分装成浓度为1×107CFU/mL BCG菌液备用。

1.3 动物模型构建与分组处理

将15只大鼠在适宜洁净的饲养间适应性饲养3周,按照随机数字表法分为感染组(12只)和正常对照组(3只)。感染组大鼠背部皮下隧道样注射弗氏完全佐剂0.2 mL,3周后皮下注射BCG菌液0.2 mL,建立大鼠结核性创面模型。正常对照组大鼠未经任何处理。

1.4 观察指标

1.4.1 大体观察

分别于感染第8、15、32、43天,大体观察感染组大鼠注射部位皮肤情况并拍照。

1.4.2 局部组织情况

分别于感染第8、15、32、43天大体观察后,用颈椎脱臼法处死感染组3只大鼠,取注射部位皮肤组织,体积分数10%甲醛固定24 h后进行包埋。正常对照组正常喂养3周后同前处死,取对应组织进行固定包埋(方法同前)。取正常对照组及感染组大鼠各时间点石蜡组织进行切片(厚度约4 μm),行常规HE染色,400倍光学显微镜下观察细胞排列、坏死及炎症等情况。取感染第43天感染组大鼠石蜡组织同前进行切片,石碳酸品红染液室温染色30 min,冲洗至液体呈无色。滴加亚甲蓝复染液,室温染色1 min,冲洗至液体呈无色。行常规脱水、透明、封片,于600倍和1 000倍光学显微镜下观察组织中细菌分布情况。

2. 结果

2.1 大体观察

感染组大鼠感染第8天,可见注射部位皮肤稍隆起、皮下形成脓肿,见图1A。随着感染时间的延长,脓肿物体积逐渐增大。感染第15天,注射部位皮肤明显隆起、皮下脓肿较感染第8天时明显增大,见图1B。感染第32天,注射部位隆起的脓肿出现破溃、脓肿表面呈火山口样外观,破溃处可见脓性分泌物,见图1C。感染第43天,脓肿破溃处无愈合倾向,脓肿较感染第32天增大,见图1D。感染第43天时完整切除脓肿,挤压脓肿物可见长条形类似乳酪状脓性分泌物由皮肤破溃处溢出,见图1E, 1H。

2.2 局部组织情况

正常大鼠皮肤组织细胞排列规律,未见炎症细胞浸润,见图2A。感染组大鼠感染第8天,可见细胞分布杂乱、大量聚集、细胞核呈融合趋势,见图2B。感染第15天,可见肉芽肿形成、炎症细胞呈同心圆状排列,见图2C。感染第32天,肉芽肿数量增多,在细菌聚集区域可见大量细胞被破坏,见图2D。感染第43天,细胞排列疏松,部分细胞坏死,见图2E。对感染第43天的组织行抗酸染色,可见组织内存在大量细菌,细菌在组织内呈团簇样聚集(图3A),高倍镜下可以看到大量呈杆状的细菌菌体聚集在病灶中(图3B)。

3. 讨论

早期,研究者为了寻找实验条件有限时肺结核研究的替代模型,使用结核杆菌建立了动物皮肤液化和坏死模型[10, 11]。随着临床对结核性创面的重视,目前研究的皮肤结核动物有兔子、小鼠、大鼠、斑马鱼、猴等[12, 13, 14, 15, 16],本研究团队也针对结核性创面进行了动物实验的探索[12, 13, 14]。Zhang等[17]使用兔模型评价了不同分枝杆菌的毒力,BCG活菌较H37Ra或耻垢分枝杆菌活菌诱导的病灶面积明显扩大,经过灭活的BCG依然比灭活的H37Ra或耻垢分枝杆菌诱导肉芽肿更明显。兔体型较大、需占用大量饲养空间、实验操作不方便,斑马鱼虽然饲养方便但形成创面所需时间较长。高剂量BCG活菌(5×106 CFU)可引起兔皮肤组织液化和溃疡[18],中剂量BCG活菌(5×104 CFU)可诱发兔皮肤组织形成肉芽肿[17]。本研究既要使大鼠皮肤形成破溃,又要探索使用较低的接种浓度保障安全性,故选用了2×106 CFU的接种量,更低的接种浓度能否引起大鼠皮肤破溃还需要进一步研究。BCG活菌引起兔皮肤结核在11 d左右达到高峰并形成液化[19],经灭活的BCG引起的兔皮肤结核在35 d后病变缓慢消退并愈合[17],有研究将42 d[20]或56 d[21]作为动物皮肤结核取材的最长时间,而海分枝杆菌引起斑马鱼结核创面形成的平均时间为59 d[14]。本研究最长的观察时间为感染后第43天,未观察到自愈倾向,更长时间的观察有待于进一步研究。

因结核杆菌标准毒株H37Rv对实验条件要求较高,更多研究者选择BCG作为动物实验[18,22]和细胞实验[23]中模拟结核菌感染的病原体,使用低毒性的BCG可以最大限度地保障实验环境及人员的安全。大鼠饲养方便,容易获得,实验试剂供应充足,大小适中便于实验操作和观察。本研究团队前期使用BCG活菌成功建立了大鼠皮肤结核模型[13],证实使用大鼠作为结核创面模型的可行性,在此基础上进行了多次建模实验,每只大鼠均可稳定地形成局部脓肿并最终破溃。前期研究显示BCG菌(1×107CFU)引起的大鼠结核创面在感染第15天仍有局部红肿[13],提示局部红肿的急性炎症表现可能与接种菌量较大有关,为了建立更接近于临床的慢性结核性创面模型,本研究使用较低的接种剂量(2×106 CFU)和隧道样注射方法,在第32天可以形成结核性创面破溃表现。该方法更容易形成局部脓肿、局部炎症反应轻,更符合慢性病灶的特点。该动物模型外观符合结核性创面的临床表现,感染第8天可见注射部位皮下脓肿形成、脓腔内可见黄绿色的黏稠脓液;感染第15天皮下脓肿较前明显增大;感染第32天脓肿出现破溃,破溃后脓肿断层剖面可见皮下形成脓性隧道与外界相通;感染第43天,脓肿破溃处未见愈合倾向。该动物模型符合结核性创面的实验室诊断标准,镜下可见感染灶部位有炎性浸润及多核巨细胞,对其组织进行抗酸染色,结果为阳性。

综上所述,本研究选用了BCG对大鼠进行建模,具有安全性、可重复性、稳定性、可控性、可靠性及对疾病的代表性,为后续研究提供了稳定的动物模型实验平台,探索使用更小接种菌量和更短的感染时间可以有效缩短研究周期、提高科研效率,这可能成为今后结核性创面动物模型的研究趋势。

本研究的不足之处:因实验条件所限,未对该模型进行深入的细胞及分子生物水平研究。本研究采用建模动物的清洁级为SPF级,针对不同免疫状态下动物建模后的表现以及BCG是否会引起动物其他系统的播散性感染,有待进一步研究。

戚欣欣、刘璐:实验操作、论文撰写;杨云稀、黄佳敏:数据整理与分析;孙炳伟:研究指导、论文修改、经费支持所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突 -

参考文献

(34) [1] GreenhalghDG. Management of burns[J]. N Engl J Med, 2019, 380(24): 2349-2359. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1807442. [2] PavoniV,GianeselloL,PaparellaL,et al.Outcome predictors and quality of life of severe burn patients admitted to intensive care unit[J].Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med,2010,18:24.DOI: 10.1186/1757-7241-18-24. [3] 戚欣欣,杨云稀,孙炳伟.严重烧伤患者早期外周血中性粒细胞趋化功能变化及影响因素[J].中华烧伤杂志,2020,36(3):204-209.DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn501120-20190801-00329. [4] ZhangP,ZouB,LiouYC,et al.The pathogenesis and diagnosis of sepsis post burn injury[J/OL].Burns Trauma,2021,9:tkaa047 [2021-12-05].https://academic.oup.com/burnstrauma/article/doi/ 10.1093/burnst/tkaa047/6128653?login=true.DOI:10. 1093/burnst/tkaa047. [5] PerssonBP,HalldorsdottirH,LindbomL,et al.Heparin-binding protein (HBP/CAP37) - a link to endothelin-1 in endotoxemia-induced pulmonary oedema?[J].Acta Anaesthesiol Scand,2014,58(5):549-559.DOI: 10.1111/aas.12301. [6] GierlikowskaB,StachuraA,GierlikowskiW,et al.Phagocytosis, degranulation and extracellular traps release by neutrophils-the current knowledge, pharmacological modulation and future prospects[J].Front Pharmacol,2021,12:666732.DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2021.666732. [7] GautamN,OlofssonAM,HerwaldH,et al.Heparin-binding protein (HBP/CAP37): a missing link in neutrophil-evoked alteration of vascular permeability[J].Nat Med,2001,7(10):1123-1127.DOI: 10.1038/nm1001-1123. [8] YangY,LiuL,GuoZ,et al.Investigation and assessment of neutrophil dysfunction early after severe burn injury[J].Burns,2021,47(8):1851-1862.DOI: 10.1016/j.burns.2021.02.004. [9] LiL,PianY,ChenS,et al.Phenol-soluble modulin α4 mediates Staphylococcus aureus-associated vascular leakage by stimulating heparin-binding protein release from neutrophils[J].Sci Rep,2016,6:29373.DOI: 10.1038/srep29373. [10] VincentZL,MitchellMD,PonnampalamAP.Regulation of TIMP-1 in human placenta and fetal membranes by lipopolysaccharide and demethylating agent 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine[J].Reprod Biol Endocrinol,2015,13:136.DOI: 10.1186/s12958-015-0132-y. [11] XiaoW,WangL,HowardJ,et al.TIMP-1-mediated chemoresistance via induction of IL-6 in NSCLC[J].Cancers (Basel),2019,11(8):1184.DOI: 10.3390/cancers11081184. [12] JungK.A strong note of caution in using matrix metalloproteinase-1 and its inhibitor, TIMP-1 in serum as biomarkers in systolic heart failure[J].J Intern Med,2008,264(3):291-293.DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01952.x. [13] JordánA,RoldánV,GarcíaM,et al.Matrix metalloproteinase-1 and its inhibitor, TIMP-1, in systolic heart failure: relation to functional data and prognosis[J].J Intern Med,2007,262(3):385-392.DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01823.x. [14] JayasankarV,WooYJ,BishLT,et al.Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase activity by TIMP-1 gene transfer effectively treats ischemic cardiomyopathy[J].Circulation,2004,110(11 Suppl 1):SII180-186.DOI: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000138946.29375.49. [15] MarchesiC,DentaliF,NicoliniE,et al.Plasma levels of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J].J Hypertens,2012,30(1):3-16.DOI: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834d249a. [16] WürtzSO,SchrohlAS,MouridsenH,et al.TIMP-1 as a tumor marker in breast cancer--an update[J].Acta Oncol,2008,47(4):580-590.DOI: 10.1080/02841860802022976. [17] LambertE,DasséE,HayeB,et al.TIMPs as multifacial proteins[J].Crit Rev Oncol Hematol,2004,49(3):187-198.DOI: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.09.008. [18] JungKK,LiuXW,ChircoR,et al.Identification of CD63 as a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 interacting cell surface protein[J].EMBO J,2006,25(17):3934-3942.DOI: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601281. [19] OrbanC. Diagnostic criteria for sepsis in burns patients[J]. Chirurgia(Bucur),2012,107(6):697-700. [20] WhiteCE,RenzEM.Advances in surgical care: management of severe burn injury[J].Crit Care Med,2008,36(7 Suppl):S318-324.DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31817e2d64. [21] BlindermanC,LapidO,ShakedG.Abdominal compartment syndrome in a burn patient[J].Isr Med Assoc J,2002,4(10):833-834. [22] 宋明明,刘璐,戚欣欣,等.肝素结合蛋白增加烧伤早期血管通透性的机制研究[J].中华危重病急救医学,2020,32(3):330-335.DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn121430-20200123-00248. [23] PeetersY,VanderveldenS,WiseR,et al.An overview on fluid resuscitation and resuscitation endpoints in burns: past, present and future. Part 1 - historical background, resuscitation fluid and adjunctive treatment[J].Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther,2015,47 Spec No:s6-14.DOI: 10.5603/AIT.a2015.0063. [24] PeetersY,LebeerM,WiseR,et al.An overview on fluid resuscitation and resuscitation endpoints in burns: past, present and future. Part 2 - avoiding complications by using the right endpoints with a new personalized protocolized approach[J].Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther,2015,47 Spec No:s15-26.DOI: 10.5603/AIT.a2015.0064. [25] 黄跃生.严重烧伤脏器损害综合防治的思考[J].中华烧伤杂志,2020,36(8):647-650.DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn501120-20200521-00278. [26] MufsonMA.Pneumococcal pneumonia[J].Curr Infect Dis Rep,1999,1(1):57-64.DOI: 10.1007/s11908-999-0011-9. [27] ConteMS,DesaiTA,WuB,et al.Pro-resolving lipid mediators in vascular disease[J].J Clin Invest,2018,128(9):3727-3735.DOI: 10.1172/JCI97947. [28] MikelisCM,SimaanM,AndoK,et al.RhoA and ROCK mediate histamine-induced vascular leakage and anaphylactic shock[J].Nat Commun,2015,6:6725.DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7725. [29] LiuL,ShaoY,ZhangY,et al.Neutrophil-derived heparin binding protein triggers vascular leakage and synergizes with myeloperoxidase at the early stage of severe burns (with video)[J/OL].Burns Trauma,2021,9:tkab030[2021-12-05].https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34646891/.DOI: 10.1093/burnst/tkab030. [30] 何兴凤,伍国胜,罗鹏飞,等.脓毒症血管通透性分子调控机制研究进展[J].中华烧伤杂志,2020,36(10):982-986.DOI: 10.3760/cma.j.cn501120-20190724-00308. [31] SchmidtEP,YangY,JanssenWJ,et al.The pulmonary endothelial glycocalyx regulates neutrophil adhesion and lung injury during experimental sepsis[J].Nat Med,2012,18(8):1217-1223.DOI: 10.1038/nm.2843. [32] PagenstecherA,StalderAK,KincaidCL,et al.Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitor genes in lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxemia in mice[J].Am J Pathol,2000,157(1):197-210.DOI: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64531-2. [33] CowlandJB,BorregaardN.Granulopoiesis and granules of human neutrophils[J].Immunol Rev,2016,273(1):11-28.DOI: 10.1111/imr.12440. [34] FisherJ,LinderA.Heparin-binding protein: a key player in the pathophysiology of organ dysfunction in sepsis[J].J Intern Med,2017,281(6):562-574.DOI: 10.1111/joim.12604. -

2 3种分组处理后人脐静脉血管内皮细胞的TIMP-1的mRNA和蛋白表达。2A.4组细胞中TIMP-1 mRNA表达箱式图[样本数为3,M(Q1,Q3)];2B.蛋白质印迹法检测的2组细胞中TIMP-1蛋白表达条带图;2C.培养48 h后4组细胞培养上清液中TIMP-1蛋白表达箱式图[样本数为3,M(Q1,Q3)]

注:TIMP-1为组织金属蛋白酶抑制物1;图2A中横坐标1、2、3、4分别为正常对照组(于适宜时间点检测,后同)、重组肝素结合蛋白(rHBP)处理12 h组、rHBP处理24 h组、rHBP处理48 h组;与正常对照组比较,aP<0.01;图2B中1、2分别为正常对照组、rHBP处理48 h组;图2C中横坐标1、2、3、4分别为正常对照组、单纯rHBP组、单纯抑蛋白酶多肽组、rHBP+抑蛋白酶多肽组,与正常对照组比较,aP<0.05;与单纯rHBP组比较,bP<0.01

3 4组从健康志愿者外周静脉血分离的中性粒细胞培养1 h后CD63蛋白表达 异硫氰酸荧光素-4',6-二脒基-2-苯基吲哚×630,图中标尺为10 μm。3A、3B、3C.分别为正常对照组(于适宜时间点检测)CD63染色、细胞核染色、CD63与细胞核染色重叠图片,细胞核完整,CD63蛋白表达较多;3D、3E、3F.分别为单纯重组组织金属蛋白酶抑制物1(rTIMP-1)组CD63染色、细胞核染色、CD63与细胞核染色重叠图片,细胞核完整,图3D中CD63蛋白表达与图3A相近;3G、3H、3I.分别为单纯佛波酯组CD63染色、细胞核染色、CD63与细胞核染色重叠图片,细胞核完整,图3G中CD63蛋白表达明显多于图3A;3J、3K、3L.分别为rTIMP-1+佛波酯组CD63染色、细胞核染色、CD63与细胞核染色重叠图片,细胞核完整,图3J中CD63蛋白表达明显多于图3A但明显少于图3G

注:CD63阳性染色为黄绿色,细胞核阳性染色为蓝色

4 4组从健康志愿者外周静脉血分离的中性粒细胞培养1 h后细胞的CD63、HBP和MPO蛋白表达。4A.细胞中CD63蛋白阳性表达率流式直方图;4B.细胞培养上清液中HBP蛋白表达箱式图[样本数为3,M(Q1,Q3)];4C.细胞培养上清液中MPO蛋白表达箱式图[样本数为3,M(Q1,Q3)]

注:rTIMP-1为重组组织金属蛋白酶抑制物1,HBP为肝素结合蛋白,MPO为髓过氧化物酶;图4B、4C横坐标中1、2、3、4分别为正常对照组(于适宜时间点检测)、单纯rTIMP-1组、单纯佛波酯组、rTIMP-1+佛波酯组;图4B中,与正常对照组比较,aP<0.01;与单纯佛波酯组比较,bP<0.05;图4C中,与正常对照组比较,aP<0.01,bP<0.05;与单纯佛波酯组比较,cP<0.05

表1 严重烧伤组患者与健康对照组志愿者一般资料比较

组别 例数/人数 性别(例) 年龄[岁,M(Q1,Q3)] 平均动脉压[mmHg,M(Q1,Q3)] 中性粒细胞计数 [×109/L,M(Q1,Q3)] 男 女 严重烧伤组 20 12 8 44.5(31.0,58.0) 92.8(85.1,100.5) 17.70(12.16,23.24) 健康对照组 20 13 7 39.5(26.0,53.0) 87.1(74.8,99.4) 7.35(6.48,8.21) 统计量值 χ2=0.11 Z=-0.21 Z=-0.66 Z=-3.17 P值 0.744 0.827 0.513 0.034 注:1 mmHg=0.133 kPa 期刊类型引用(0)

其他类型引用(1)

-

下载:

下载:

下载:

下载: